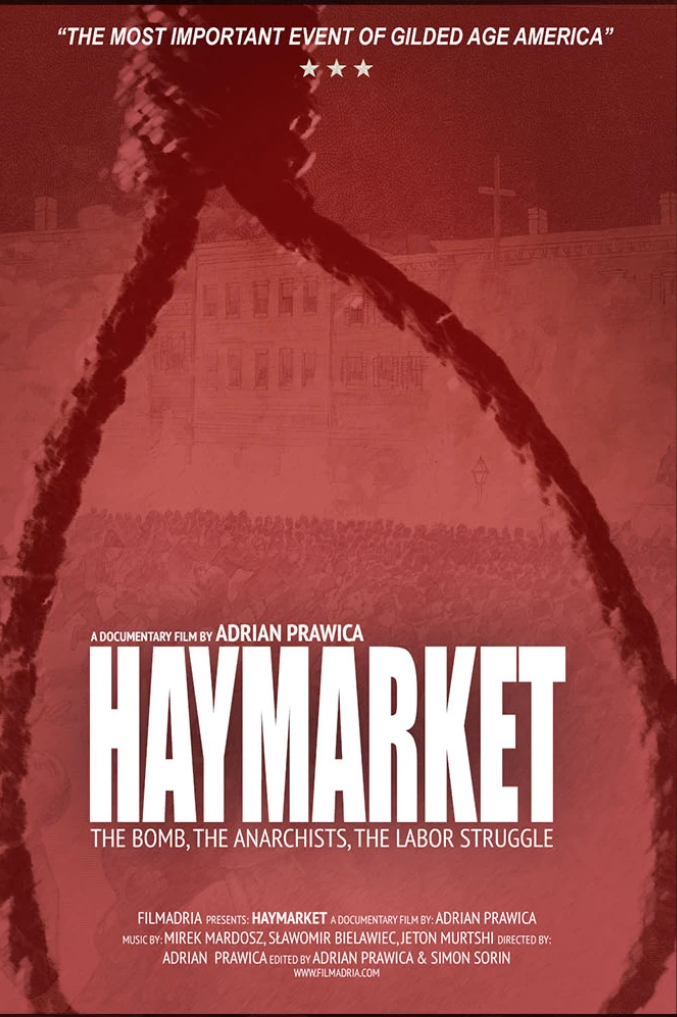

On May 4th, 1886, workers gathered in response to incidents of violence provoked by business owners and enacted by police that had taken place in the days prior. Intended to be a peaceful assembly, a bomb was thrown into the crowd, erupting chaos amid the smoke and police crossfire. In what came to be known as the Haymarket Affair, this evening became the first incident in recorded American history in which a bomb had been thrown outside of the time and context of war. Though a largely neglected instance in history books today, at the time its explosion echoed in headlines the world over. Adrian Prawica’s film Haymarket: The Bomb, the Anarchists, the Labor Struggle approaches this grim, Chicago evening from a primarily historical perspective.

Haymarket’s retelling of these events remains linear and coherent, concise and level. Each of the few historians interviewed for the film take a turn at providing a high-level overview of the circumstances surrounding the Haymarket Affair. The subjects detail their accounts of what those who were wrongly tried, convicted, and ultimately hanged could have endured. Given this level of detail, Haymarket aids the viewer in contextualizing the experiences of the Haymarket Martyrs—placed against the odds of a predetermined fate. After exploring the trial, the film briefly touches on the pacifying effect that the aftermath would have on the labor movement in the decades to follow. This insight, albeit brief, is a valuable one, especially when tethered to the manner in which it explains the anti-communist and anti-socialist fabric being stitched into the seams of the American consciousness.

Prawica’s Haymarket, at moments, succeeds in challenging common tropes in state-endorsed retellings of the Haymarket Affair. In one instance the film goes so far as to deconstruct the vilified caricature of the anarchist, still often encountered in the media. As opposed to the ever-looming, mustache twirling character cartooned throughout the ages, the portrait painted is one of workers struggling against an unfair and oppressive system. To do so, Haymarket highlights each Martyr’s background—thus doing away with the illusion of this Snidely Whiplash-reminiscent image. Though this assertion is welcome, and for the Martyrs sake, overdue: the clarity that this, or any single documentary could provide will remain a far cry from its undoing.

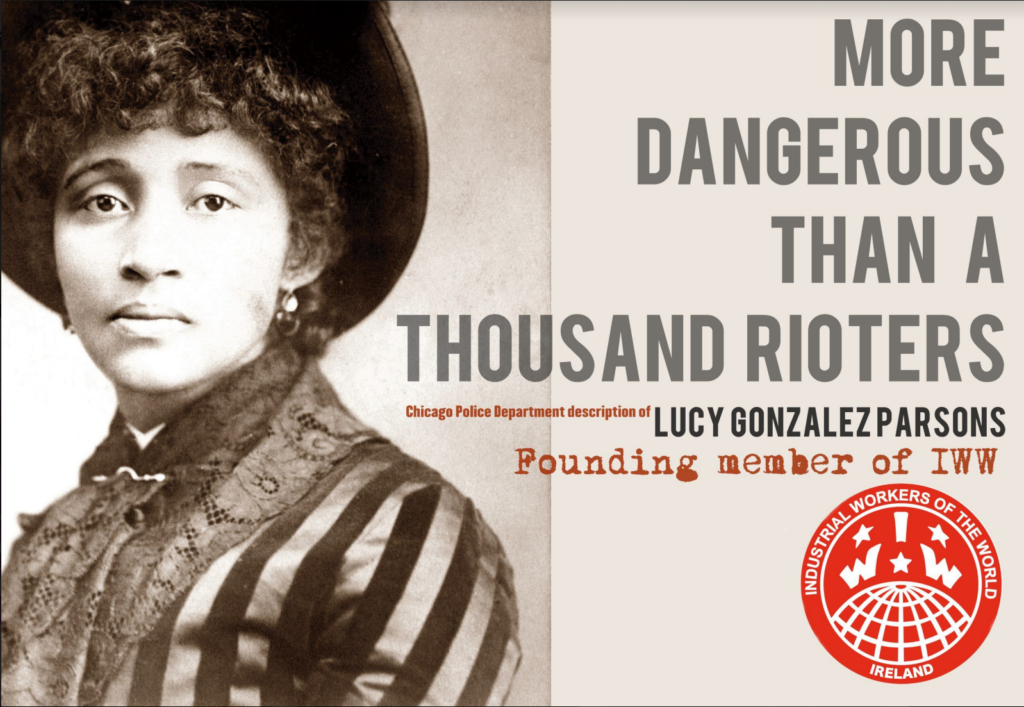

That in mind, we as the viewers are only offered a cursory description of what the defendants believed. The film never truly dives into a substantive examination of anarchism or socialism. Without this explanation the viewer is not exposed to what would come to be known as revolutionary syndicalism. Though the term had yet to be coined, it was that principle in which these Martyrs believed. This leaves the question as to why these workers would be willing to die, unanswered. Consequently, the viewer is kept in the dark to the passions held in the hearts of each defendant, making the absence of those values as notable as the film’s neglect of the IWW itself.

While it’s true the foundation of the IWW would not take place until almost twenty years after their execution, many principles alive in the I.W.P.A (International Working People’s Association) would go on to inform Wobbly thinking. Neglecting to mention the I.W.P.A, in which the defendants participated, also does the film a great disservice. It is not until the closing credits that the film offers a written summary of Neebe’s life after prison—only then finally drawing to attention the IWW, solely under the guise of his membership.

Lucy Parsons, much like the organization she went on to found, is hardly discussed. Quoted once by a single interview subject, she is otherwise reduced to her relevance as Albert’s widow. This solitary perspective shines a bright spotlight on both the lack of diversity of those interviewed for the film. Should the director have pulled from a wider range of those with insight, we would have received a deeper understanding of Lucy Parsons, the IWW, and how these events shape labor today. Such lapses, in both a conceptual and literal sense, could leave a familiar viewer feeling hollow—as if the most central piece to this story is missing. Truth be told, it is. The core values for which these men sacrificed their lives, is given, at most, cursory consideration.

The documentary inaccurately specifies that one defendant, Louis Lingg, chose not to speak on his own behalf. As catalogued in the court transcripts, and later published in Albert Parsons’ posthumous book Anarchism: Its Philosophy and Scientific Basis, Lingg articulated, at some length, his feelings on both the bombing, and the origin of the bomb, itself. Yet, the film asserts that the bomb was made by Lingg as a matter of fact. In reality, Lingg brashly utilized his time to criticize the quality of the bomb thrown to be inferior to that of his own. Additionally, Lingg aggressively advocated that social movements act in self-preservation in his address to the court.

“But the fact is, that at every attempt to wield the ballot… you have displayed the brutal violence of the police club, and this is why I have recommended rude force, to combat the ruder force of the police.” Here, we witness Lingg state in explicit terms his belief that working people should use violence in the face of an ever-advancing militarized state. It is the story of Lingg and his fellow workers tried on the world’s stage that gave credence to what we understand now to be the neo-liberal doctrine of non-violence. In their time, it became their loss which set the precedent for the dangerous consequence of revolutionary thinking. Conversely, today we are presented the alternative—that revolutionary thought is the danger, not the consequences it is met with.

Somewhat to the film’s benefit, Prawica never gets too far into the weeds of “who threw the bomb.” The director’s chair thankfully isn’t utilized to sit on high—squarely pointing at who the filmmakers consider to be responsible. It is surprising, however, to find the name George Meng absent from the listed possibilities, no matter how brief the exploration. The suspect became the most likely to historian Paul Avrich, once new information surfaced, following the release of his 1984 book The Haymarket Incident, in which Meng had yet to come to his attention.

Accidental or deliberate, all of these omissions work together to create a concise sense of finality which undermines both the documentary, and a movement that is as relevant today as it was in 1887. Given this, an unfamiliar viewer might gather the impression that this moment, and the Martyrs’ execution, brought closure to the struggle for workers’ rights. And while evoking that feeling of closure may remain an important staple in works of fiction, it is reality in which we reside—where our struggle for global emancipation continues. Regardless, it is the crux of the documentary that stays on message: that the fate Parsons, Spies, Fischer, Engel, Lingg, Schwab, Neebe, and Fielden suffered is fixated in history. All in all, the film hits the mark it aims to. We receive an 86-minute overview of the time period, the incident, and the trial. However unfortunate it is that the last spoken words of Haymarket dismiss the necessity of revolutionary action and seethe with American exceptionalism—any retelling of these events deserves recognition. It just so happens that the viewer’s enjoyment of this film might simply be contingent upon their level of familiarity with the incident.

Paul Scanty is the co-chair of the Education & Outreach Committee of the Greater Chicago IWW, a writer, occasional speaker, and vocalist for Chicago hardcore outfit The Ableist. Connect with Paul via social media at @PaulScanty