Jeffrey B. Perry was an independent working class activist, union militant, scholar, and archivist. He was active in the rebellion of the 1960s-70s and since then dedicated his life to various struggles for economic, political, and social justice. He championed militancy, anti-capitalism, direct action, and mass social movements in the US and internationally. He was a prolific writer and researcher, and is credited with unearthing the largely forgotten history of Black revolutionary socialist Hubert Harrison. He dedicated much of his scholarly work on who he viewed were two of the most important thinkers on race and class in American history: Hubert Harrison and Theodore W. Allen.

Perry authored Hubert Harrison: The Voice of Harlem Radicalism, 1883-1918, and Hubert Harrison: The Struggle for Equality, 1918–1927 (both published by Columbia University Press). He edited and wrote introductions for A Hubert Harrison Reader (Wesleyan University Press) and Theodore W. Allen’s The Invention of the White Race (2 volumes, Verso Books).

Jeffrey B. Perry was a true believer in and supporter of the Industrial Workers of the World, both historically and today. We are honored to publish this short biographical sketch he wrote of revolutionary Black socialist and Wobbly Hubert Harrison. Perry passed away in 2022. We encourage you to honor his incredible legacy by reading his work which can be found on his website, and read his books on Hubert Harrison, and the works of Theodore W. Allen. And as always, match that theory and history with action, with praxis – just as Jeffrey B. Perry would do.

–Brendan Maslauskas Dunn.

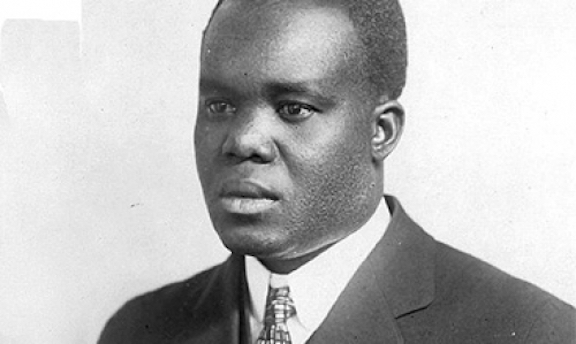

Hubert Henry Harrison (1883-1927) was a brilliant working class writer, orator, editor, educator, book reviewer, and race- and class-conscious radical internationalist. He was described as an intellectual giant by historian Joel A. Rogers and as the father of Harlem radicalism by labor and civil rights activist A. Philip Randolph.

Harrison was born in St. Croix, Danish West Indies to an immigrant and laboring class Barbadian mother and a formerly enslaved Crucian father. He received the equivalent of a ninth grade education in St. Croix where he learned customs rooted in African communal systems, interacted with immigrant and native-born working people, and grew with an affinity for the poor and with the belief that he was equal to any other. He was familiar with the Crucian people’s history of direct-action mass struggle, including the successful 1848 enslaved-led emancipation victory, the 1878 island-wide “Great Fireburn” rebellion in which “Queen Mary” Thomas and other women played prominent roles, and the October 1879 general strike.

In 1900 Harrison immigrated to the United States where he was “shocked” by lynching and the virulence of white supremacy, two manifestations of racial oppression that contrasted sharply with what he knew in St. Croix. While working full time he attended high school at night, excelled as a student, and began writing letters to The New York Times.

Harrison was an autodidact who soon became active in lyceums where working class Afro-Caribbean immigrants and U.S.-born African Americans met and exchanged ideas in a vibrant intellectual atmosphere that nurtured friendships and encouraged the right to openly criticize what one believes is wrong.

In 1907 he began work as a postal clerk and moved to Harlem and in April 1909, he married Irene Louise (“Lin”) Horton, whose family was from Antigua, British West Indies and had spent time in Puerto Rico. They had five children between 1910-1920.

By the end of his first decade in New York Harrison, influenced by the Freethought Movement, had broken from organized religion and turned to a scientific approach to address social problems. He was active with the inter-racial Sunrise Club, Single Taxers, Socialists, and Freethinkers.

Between 1911 (after being fired by the Post Office) and 1914 Harrison was the foremost Black activist, orator, and theoretician in the Socialist Party of New York. Harrison was an articulate critic of capitalism, and he wrote a pioneering series of articles on socialism and Black people in the socialist New York Call and the International Socialist Review. He emphasized that the “Negro” was more essentially proletarian than any other group and that it was the duty of socialists to oppose racial prejudice. He also helped found the Colored Socialist Club, an unprecedented outreach effort by U.S. socialists to Black people, and publicly posed the question “Southernism or Socialism?” prior to the 1912 Socialist Party Convention.

Harrison’s 1912 position that “the duty to champion the cause of the Negro” was socialism’s crucial test anticipated a similar statement by W. E. B. Du Bois in 1913. In his writings Harrison maintained that racism was not innate, but that it was a tool to divide workers, and that it was in the interests of American capitalists to preserve the inferior economic status of Black people to use as a club against other workers, to keep wages down and to foster disunity in the working class. He stressed that Black people were the “touchstone” of democracy and that the struggle for democracy and equality for African Americans had revolutionary potential – a prescient analysis that foreshadowed developments in the 1960s when the civil rights movement and Black liberation struggle served as a catalyst for other movements for progressive social change.

Harrison also gained a reputation as a popular and unrivaled soapbox orator. He spoke as many as twenty-three times a week during the 1912 Presidential campaign of Socialist Eugene V. Debs. He spoke for three hours on socialism at Broad and Wall Streets in front of the Stock Exchange (in an early Occupation of Wall Street), before fifty thousand people at Union Square, and throughout New York City and New York State, New Jersey and Connecticut. He increasingly moved to the left within the Socialist Party, supported the militant, direct-action-oriented Industrial Workers of the World, and was a featured, and extremely militant, speaker for the union (along with Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, “Big Bill” Haywood, and others), and the only Black speaker, at the historic 1913 Paterson silk workers strike. Socialist Party statements and practice led him to conclude, however, that the Socialist Party, like organized labor, put the “white” race first, before class.

After leaving the Socialist Party in 1914 Harrison was active with freethought and secular movements, free speech and birth control struggles, the anarchist-influenced Modern School, and with his own Radical Forum. In 1915-1916, after writing probing theater reviews and delivering talks on the racial significance of World War I, he concentrated work in Harlem. Here he urged race unity from the bottom up and pioneered the tradition of Harlem soap-box oratory subsequently carried on by Randolph, Marcus Garvey, famed Scottsboro orator Richard B. Moore, and Malcolm X. Some of his early writings from the freethought publication The Truth-Seeker, the Jewish socialist monthly Die Zukunft, the Socialist Party Call, and the International Socialist Review were reprinted in his book The Negro and the Nation (1917).

In 1917 Harrison founded the first organization, The Liberty League, and the first newspaper, The Voice: A Newspaper for the New Negro, of the “militant New Negro Movement.” This race conscious, internationalist, mass based movement sought social justice, civic opportunity, political equality, and economic power for Black people. It also viewed itself as consciously breaking from “old Negro” leadership, laid the basis for the Garvey movement, and contributed significantly to the climate that nurtured Alain Locke’s 1925 publication, The New Negro. The Liberty League responded to Woodrow Wilson’s call to war to “Make the World Safe for Democracy” with a call to “Make the South Safe for Democracy.” In response to lynching, segregation, disfranchisement, peonage, and discrimination the League’s program called for enforcement of citizenship and voting rights, federal anti-lynching legislation, militant resistance (including armed self-defense) to attacks, and a political voice. Harrison advocated that “New Negroes” control their own resources for racial uplift. He also called a large protest meeting in Harlem after the white supremacist “pogrom” in East St. Louis, Illinois (which is less than 16 miles from Ferguson, Missouri) in July of 1917. Garvey and other leading activists, including future leaders of the Garvey movement, joined the Liberty League. The organization adopted a black, brown, and yellow tri-color flag, which represented the three colors of the Black race in America and of people of color worldwide.

Harrison became a nationally recognized Black protest leader in June 1918 when he and William Monroe Trotter co-chaired the Liberty Congress, the major Black protest effort during World War I. The Congress drew men and women from thirty-five states and demanded true democracy, federal anti-lynching legislation, and an end to segregation and disfranchisement. The Liberty Congress’s wartime demands served as precursors to the March on Washington Movement during World War II and the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom during the Vietnam War. Between 1916 and 1920 Harrison also spoke in Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Washington, DC, and Virginia.

In 1919 Harrison edited The New Negro: A Monthly Magazine of a Different Sort, which sought to express the international consciousness of the people of color, particularly of Black people. In 1920, he became principal editor of Garvey’s Negro World newspaper, which he re-shaped into a leading radical race-conscious political and literary publication. Harrison wrote on Africa, the Caribbean, the Mideast, Asia, the Americas, history, politics, literature, theater, religion, and science; criticized capitalist imperialism; advocated a “Colored International;” and initiated “Poetry for the People,” “Book Review,” and “West Indian News Notes” sections. He also supported Black writers and artists including J. A. Rogers; poets Claude McKay (who was also a Wobbly) and Andy Razaf; sculptor Augusta Savage; actor Charles Gilpin; and musician Eubie Blake. In August 1920 Harrison’s When Africa Awakes: The “Inside Story” of the Stirrings and Strivings of the New Negro in the Western World was published. At this time, Harrison grew critical of Garvey, and stopped serving as managing editor of the Negro World after the August 1920 Universal Negro Improvement Association Convention and stopped writing for the paper in 1922. By that time he had played significant roles in the largest class radical movement and the largest race radical movements of his era.

After leaving the Negro World Harrison wrote and lectured widely. Though he was a trailblazing book reviewer and literary critic during the period known as the Harlem Renaissance, he questioned the “Renaissance” on its willingness to accept standards from white society and on its claim to being a rebirth. He lectured for the New York City Board of Education from 1922-1926, taught World Problems of Race at the Institute for Social Study in Harlem in 1926, and spoke at universities, libraries, community forums, and street corners as well as in New Jersey, Indiana, Illinois, and Massachusetts. He became a U. S. citizen in 1922 and in 1924 served as a founder of the Virgin Islands Committee, which promoted economic and political reconstruction of the Virgin Islands. Maintaining his political independence, Harrison worked with Democrats, Single Taxers, Farmer Laborites, and Communists. A bibliophile and advocate of free public libraries, he was also a founding officer of the committee that helped develop the 135th Street Public Library into a center for Black studies, subsequently known as the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

In 1924 Harrison founded the broadly unitary International Colored Unity League, which emphasized Black solidarity and self-support, advocated race first politics, and sought to enfranchise Black people in the South. Its economic program included cooperative farms, stores, and housing, and its social program included scholarships for youth and opposition to restrictive laws. The League also made an innovative call for a separate state or states for establishing a homeland for Black people in the United States.

In 1927 Harrison edited the League’s Embryo of the Voice of The Negro and then The Voice of the Negro until shortly before his unexpected December 17 death at Bellevue Hospital. At his massive Harlem funeral Richard B. Moore described Harrison as the “Black Socrates” and Arthur Schomburg presciently eulogized that Hubert Harrison was “ahead of his time.”

This article was originally submitted to Love and Rage Media, an independent media outlet run by Wobblies in Utica, NY. It was unfortunately never submitted until now when editors graciously sent this article to The Industrial Worker – a fitting publication to honor the legacy of Hubert Harrison and Jeffrey B. Perry.