Towards a world without prisons.

Over the course of the past few weeks, you might have heard about concepts that, on the face, sound jarring. Abolishing the police? Abolishing prisons? Who will keep us safe? Where will the bad guys go to prevent them from harming more people?

I have been a prison abolitionist for two years now and part of what changed my mind about accepting abolitionist ideals was finally researching enough to imagine the future without prisons, to have a picture in my mind of what the world could be instead of what it is.

Now, as a caveat, my image of prison abolition is neither universal nor finite. A world without prisons means local communities decide what they need and those needs will vary by community; it could look like a hundred or even a thousand different things at the same time. Maybe only one community will find my vision of prison abolition to be the best one, or dozens might while everyone else might not. And that’s amazing! Part of accepting abolition is accepting that our lives and economy are incredibly carceral and until we learn to predict the future, we must recognize that decarceration will probably come with unexpected outcomes. However, an abolitionist knows that communities are capable of handling unforeseen challenges and trusts that whatever comes of decarceration will surely be preferable to the devastating effects of our current carceral system.

Why Abolition?

Once we realize our systems of power are flawed, it can be comforting to believe in easy, simple solutions. We might think to ourselves, if only we could get rid of private prisons, or if only we could change the way communities are policed, then things will not need to change much to solve the problem. This is, I’m sorry to say, false hope. There are no quick fixes or easy solutions. Here’s why reform can’t solve the issues with our carceral system:

- The function of the police is problematic in and of itself. As you might have heard in the past, the American policing system evolved from slave patrols and, in many ways, still serves to confine Black Americans to involuntary servitude today. Even if you believe — in the face of clear structural racism embedded in the institution itself — that the police can be reformed, you must at least concede the job of a police officer includes choosing who to protect from whom. Next time you watch a video documenting police conduct, observe who the police choose to defend and who they choose to identify as the aggressor. There’s a reason many leftists refer to cops as the armed wing of capital: police officers consistently side with right-wing agitators and capitalist property over the people they are said to protect. This is not because individual police officers are making choices; it is their job to defend the status quo (and all of the devastating things that go with it).

- The prison system is built to drift towards privatization, expansion, and worsening conditions. Our modern prison system is described by abolitionist Angela Davis as “what made the most sense at a particular time in history.” It began in Pennsylvania in the revolutionary era with the advent of the penitentiary and became standardized in the US during the 19th century. Prior to this, rather than an arbitrary length of time in prison being assigned to a crime, punishments were rooted in labor. Since then, the popular mythos has codified the prison into an inevitability, which must always exist, along with its respective police force. Many reform advocates suggest that, by doing away with the roughly 9% of privately run prisons (where conditions are worst), we can maintain the inevitable prison without its worst elements. Like other industrial complexes, however, the business of incarceration cannot be satisfied with just the status quo. Profit is so ingrained in the existence of the prison that even abolishing privatized prisons could not stop the industry’s need for fresh blood. Shaun Bauer writes in American Prison that the first instance of prison privatization occurred in the 1850’s, in tandem with the end of slavery and the beginning of racialized prisons as the main form of criminal punishment. Housing, feeding, and clothing individuals who do not contribute to the economy (except to serve in state-sanctioned sweatshops) is an expensive endeavor and state governments simply cannot maintain it. So long as prisons exist, it will always be cheaper for state governments to delegate incarceration to private corporations, ensuring conditions will always grow worse. Moreover, even if we banned the privatization of prisons, this would not be enough to satiate the needs of those companies that provide food, technology, security, contracting, and other innumerable goods and services that profit from the growth of inmate populations. As long as there is a prison, it will be beholden to private capital interests that will always undo and work around whatever reforms you might achieve.

- Incarceration is inhumane, no matter how it is done. Solitary confinement is internationally recognized as a method of torture. Many American jails basically confine entire prisons to it. We live in a world where people are captured on the street by armed militiamen and locked away in cages. Many Democrats have come around to the idea that cages are unjust for migration “crimes” and yet will still rationalize it for other crimes by imagining a hypothetical evildoer who is so vile they must be locked away. I maintain that separating a person from their family, from their community, their work, and their society, and placing them in a cage is never just, even if that cage has a moratorium on beating prisoners or allows access to education. Are these things good for the material conditions of prisoners? Of course. But are they the end goal? Are they the high ideal we should dream of in a just society? Of course not.

- This system does not bring justice. Our criminal “justice” system is racist. It is sexist. It is homophobic. It is transphobic. It is classist. It boasts an array of bigotries that not only cause the perpetrators of crime to become the victims of new crimes themselves, but also fail the original victims who go to the police for safety. When police officers show up to a house for a wellness check or to stop a crime and end up shooting the person who called them, that is not justice. When undocumented women feel they cannot report sexual assault or domestic violence because they might be turned over to Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), that is not justice. Frequently, arguments against abolition rely on the assumption that police departments and prisons do more for their communities than they actually do. In fact, the Pew Research Center finds that fewer than half of all crimes are reported and, of those reported, fewer than half are solved.

The police draw from a pool of applicants who are drawn to the police force. These individuals are the kind of people who are attracted to a job that largely consists of incarcerating people (who are disproportionately Black and Brown) and carrying a gun down the streets of poor neighborhoods. From there, they experience a real-life version of the Stanford Prison Experiment on a daily basis. As such, crime is shown to actually decrease without the police, as evidenced by statistical analysis of an NYPD strike in 2014. This is not a system which can be saved nor is it one worth saving.

Structural problems can only be solved with a change in the structure. If you understand the racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, or classism embedded in the American criminal “justice” system, you will see why it needs to be overhauled — not reformed. Attempts to reform it have left us where we are today. We can, however, completely replace the system altogether with a new one that has none of these embedded chauvinisms. One need only look to Minneapolis, which implemented seven of the currently popular “8 Can’t Wait” reform proposals on top of a number of other progressive policing reforms but still saw the brutal murder of George Floyd that engendered the current protests. We are living through the evidence that reformism will not save us from the system working as it was intended to.

A full overhaul may sound daunting, but fear not! Abolition is possible by addressing the root causes of crime. Let’s break it down: what might cause a person to commit a crime?

- They have done something that plainly should not be illegal. These crimes include protesting charges, drug possession, loitering or sleeping outside, sex work, and migration.

- They suffer from some kind of psychiatric condition. This includes addiction to drugs or alcohol and so-called sociopathy.

- They are in poverty, and this has led them to pursue crime as a means of survival.

- They want power over others. This includes crimes such as rape, murder, hate crimes, and assault.

Step 1: Eliminate Unnecessary Crimes

A number of crimes in the United States exist for arbitrary reasons and end up doing more harm than good. Why, for example, is loitering an offense? What about crimes that criminalize peaceful protests, like disturbing the peace or obstruction? The criminality of these acts is a small, if powerful, statement but what about other, more insidious criminalizations? The use and possession of drugs, rather than a public health issue, is a crime that is disproportionately enforced on poor communities, particularly Black and Brown ones. The same goes for sex work, which can put sex workers in dangerous situations if it remains illegal. Additionally, the Trump presidency has brought renewed interest in decriminalizing migration, with advocates already suggesting we abolish ICE. There is popular support for decriminalization of many drugs and of sex work, as well as opposition to anti-homeless laws and laws which restrict protesting. What is stopping us from repealing these laws and, therefore, freeing up resources to combat real crimes more effectively?

Step 2: Provide Healthcare for All

This step, at first, might sound counterintuitive. We’re talking about abolition, not healthcare! However, American prisons are the largest providers of mental health services in the country, and a disproportionate number of individuals currently arrested by the police suffer from some kind of mental illness. So, upon phasing out American prisons, we would need to replace them with hospitals and rehabilitation centers. Individuals suffering from addiction who would otherwise have been convicted of a criminal drug offense would have access to rehabilitation programs, instead of receiving prison time, which could help them overcome their dependence. People who suffer from undiagnosed or untreated mental illnesses that cause them to commit crimes would better be served in hospitals than jails anyway.

Some might call this form of hospitalization a “prison by another name,” so I will clarify that institutionalization would not exist to confine individuals suffering from mental illnesses. Much like with any other sick person, hospitalization would not be punishment, and it would not be mandated for an arbitrary amount of time by the court system. An individual would be hospitalized (if inpatient care is necessary at all) for an amount of time decided by a doctor, just as they would be with a broken leg or for a surgery. It is not a punishment, only a program with the goal of finding long term treatment that allows a person to reintegrate into their community. This includes individuals with antisocial personality disorder (colloquially referred to as sociopathy), many of whom can live wholly normal lives without experiencing empathy if given the proper care. It also includes a range of other conditions that might bring people to engage in “criminal” behavior as a result of manic episodes, hallucinations, or states of distress. Treatment should be individualized, accessible, and decarceral for all mental illnesses and addictions. By making it so, we can eliminate a lot of crime before it happens and stop recidivism for anyone who slips through the cracks.

Step 3: Combat Poverty & Introduce Diversion Programs

A number of crimes are caused by the circumstances of one’s birth. Being born into poverty means one is twenty times more likely to end up in prison than being born into wealth. It also means one’s community will be even more heavily policed, especially if it is a community of color. This combination of poverty and policing results in disproportionate incarceration for those who can afford it the least. By working to combat poverty, as should be a part of any social project, we can lessen these effects. In the meantime, however, before poverty is eradicated entirely, there will still be crimes of poverty being committed. We must begin by abolishing the police and replacing them with community solidarity and an increase in the number of public social workers, resulting in a decreased criminalization of poor communities that would free up resources for other elements of what is called a diversion program.

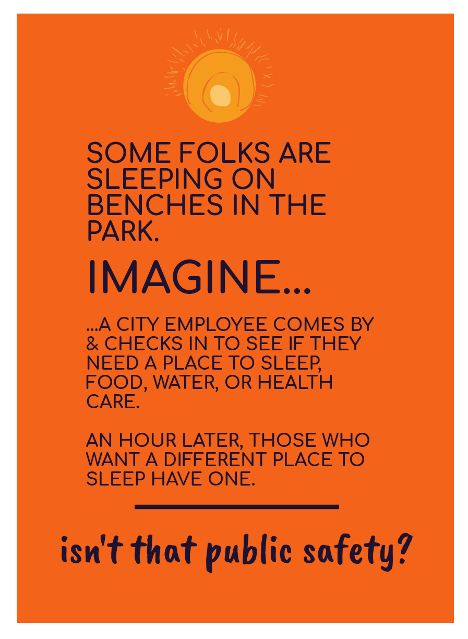

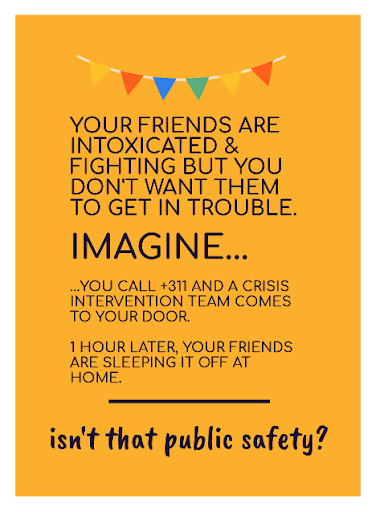

What would a diversion program do? In many cities, diversion programs are currently being used by the police as alternatives to charging suspected criminals with a crime. Instead of going to court, an unhoused person might be paired with a local nonprofit that provides housing. A person who has just overdosed is taken to a hospital and offered treatment. These programs are already in place in over 100 major American cities — the only distinction between the status quo and the abolitionist solution is that a licensed social worker or a community member be the one to call the social program for a neighbor in distress, rather than an armed defender of capital (social workers are, in some cities, already doing this and showing success). What’s more, these programs have been shown to reduce recidivism and save cities money, even with just the small scales they have been implemented under.

If you would like more examples of how a diversion program would look, Conflict Transformation has put out a fantastic set of graphics imagining a prison abolitionist world of public safety, each with an individual situation and its outcome explained. I’ve included three of them below.

Step 4: Embrace Restorative Justice

Now, what about the big scary crimes? What about the crimes with victims? What if someone steals my car or hurts me? For these offenses, it is important to remember that the police are likely not going to fix the issue if it negatively affects the status quo. Very few sexual assailants end up being charged, let alone convicted. 40% of murders go unsolved. The carceral system does not bring justice for many victims of crime, largely because it is reactionary. It only punishes; it does not prevent.

In her book, Are Prisons Obsolete?, Angela Davis posits that the true alternative to prisons is schools. This does not mean that schooling alone can prevent all crime but it does mean that decarceration begins with anti-racist education and with removing police officers from classrooms. It starts with teaching children from a young age that justice is not about making sure the bad guys get what’s coming to them, but rather about “reparation and reconciliation.” Then, we make our justice system reflect that.

Restorative justice is a response to violence and harm that centers these things and that, once again, is already being practiced effectively within our current world for workplace conflict resolution and in the juvenile “justice” system. Under a restorative justice framework, an individual who commits a crime with a victim — someone who steals from or harms another person — is given a program of activities designed to instruct that person about systems of power and their place in them. These activities might include meetings with a counselor, attending a class or lecture, reading and submitting a reflection, volunteering, or a mediated discussion with the victim of the crime and their support network. It would likely include more than one of these tasks. The goal of the process would be to ensure that the person who caused harm would not learn to fear incarceration (which doesn’t reduce crime) but instead would learn to understand what power structures and personal drives caused them to commit this crime and to put them on a path to understand themselves, their actions, and the world around them, ensuring that they would not want to commit a crime again. At the same time, the victim of the crime or victim’s family would have the opportunity to access resources and care if necessary, to sit down and speak to the person who wronged them, and to find more closure than the current system gives.

The example Davis uses in her book is Amy Biehl, an American activist in South Africa who was killed by Bantu nationalists, believing her to be an Afrikaaner. Through restorative justice, her parents eventually even became friends and colleagues with the individuals who killed her.

For my example, however, I’d like to get a bit more personal. When I was a freshman in college, like far too many young women, I was raped. I will spare the details but, in essence, it is clear looking back that this was no miscommunication. My rapist only spoke with me on Snapchat, an app that would delete my assertion that I would not have sex with him (the only evidence I had). Never mind the fact that sleeping women can’t give their consent.

I had no evidence that I did not want to sleep with him. I had no evidence that I was sleeping while he had sex with me. I knew if I went to the police, this assault would become my entire life when I just wanted it to go away. At the time, I merely wanted my assailant to understand what he was doing was wrong and not do it again, but because he was in the US on a student visa, the best case scenario our “justice” system gave me was seeing him deported. I didn’t want that. I had heard so many conversations about “women ruining men’s lives” with assault accusations, and they affected me. I was not yet a prison abolitionist; I didn’t even know what restorative justice was. But I did know the system would likely fail me, or it would fail him. Even though I wanted to hate him, I couldn’t. I still thought it might have been some kind of misunderstanding. All I wanted was to make sure it didn’t happen again.

Though I didn’t understand it at the time, I, like many victims of sexual assault, needed a prison abolitionist program. I wanted counseling for myself. I wanted him to learn about the patriarchy and rape culture. I wanted to sit down with him and have a conversation where I could look him in the eyes and get an apology, and then I wanted to go back to my life. Instead, caught between a rock and a hard place, I did nothing. And because of that, he most definitely went on to rape other women.

I’m not the only survivor who feels that the system fails us. One need only look at the slew of victims’ families opposing the death penalty for their loved ones’ murderer to see there is something disproportionate and unjust about the way our carceral system treats survivors of crime and tragedy. In the current structure, we have no say in the “justice” that is supposedly for us and can only cross our fingers for closure. Depending on how powerful or privileged the aggressor is, we likely will not even see a response to our pain at all. Our current system is an all-or-nothing punishment machine, letting the wealthy off with warnings and locking away the poor for life.

If one is Black or Brown, one need not even commit a crime to have one’s life taken. As I write, protests wage throughout the country following the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery. These innocent people were lynched by police officers and retired cops who then went on to walk free until national public outrage forced officials to charge them. There is still no guarantee that anyone will be convicted for these crimes. We live under a system which kills some for nothing and does nothing while others kill.

The fact is, our prisons and our police are working as intended. They were constructed to lock away surplus populations. They were made to defend property over people. They were designed to reinforce racial hierarchies. No matter how thorough a reform might seem, it will never be able to gut out these rancid roots because the system isn’t broken; it’s doing its job.

We cannot allow this moment of national unity and resistance to be stymied by middling proposals which suggest compromises as a starting point. We can build structures to replace police and prisons. In fact, police and prisons were themselves built as progressive alternatives to the systems before them. It is only natural that we replace an outmoded structure of racism and reaction with something more effective and humane. Will it be easy? No, but neither was abolishing slavery or abolishing segregation and those structures were just as (if not more) ingrained into the societies of their time. Those abolitionists did it because they were unafraid to demand what was needed. We can be too.

For anyone still struggling to grasp the idea of an abolitionist future, I will include now a list of other potential abolitionist worlds. As I mentioned earlier, the best part about prison abolition is that it does not have a finite proposal. If my vision isn’t your vision, perhaps someone else’s might be.

- Angela Davis

- Critical Resistance

- K Agbebiyi

- Madison Pauly

- Mariame Kaba

- MPD150

- Prison Research Education Action Project

- Ruth Wilson Gilmore

Raegan Davis is a community organizer based in Washington DC. She has written for Mondoweiss as well as the Industrial Worker and can be reached on all platforms at @theraegandavis

Photo by Sharosh Rajasekher on Unsplash