Of the many casualties stemming from the year 2020, the city of Asheville’s reputation as a cool and progressive mountain town may be one of them. For many, the erosion of this tiny North Carolina city’s image started over the summer when police began teargassing peaceful Black Lives Matter protesters. For me, however, it started right at the beginning of the year, when my supposedly lefty, “revolutionary” employers at the Asheville-based vegan plant meat company No Evil Foods began showing their true colors.

Throughout January and February, No Evil dropped thousands of dollars on expensive union-busting lawyers to propagandize workers out of wanting to unionize.

It was only a month after we lost the union election that COVID reared its ugly head – and that’s when shit really hit the fan.

With COVID worries understandably growing among the production staff, management began huddling us into meetings and assured us that they were working to sanitize everything as often as possible. “This is the safest place you can be,” our plant manager at the time told us, going on to later deny claims that the virus lingered in the air for more than a few minutes. When one worker pointed out that they were immunocompromised and expressed concerns about the challenges of social distancing in a small facility where doing so consistently is impossible, the plant manager responded by saying that if we didn’t feel comfortable being at work, we didn’t have to be there.

Sure, nobody has to work in the middle of a pandemic, but the alternative is homelessness and starvation – and employers know this.

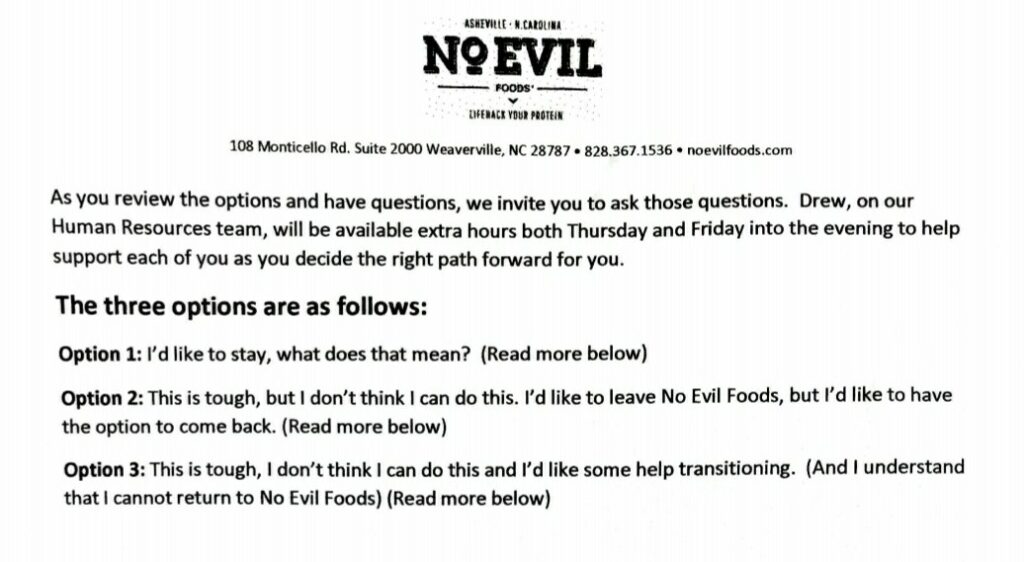

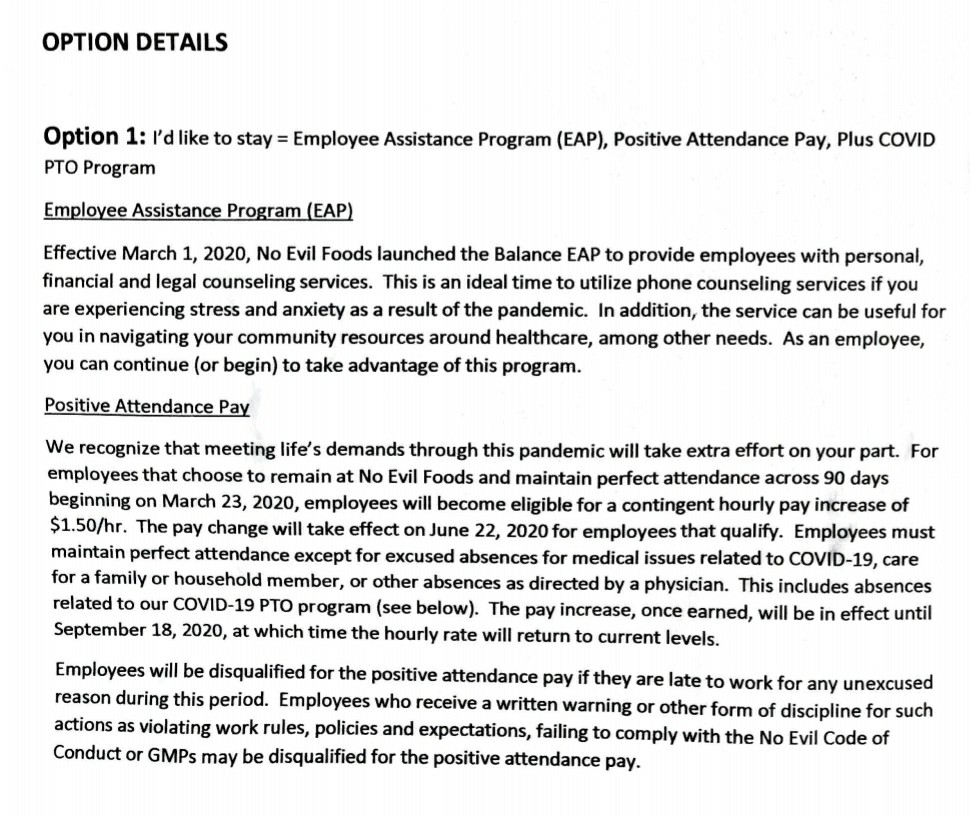

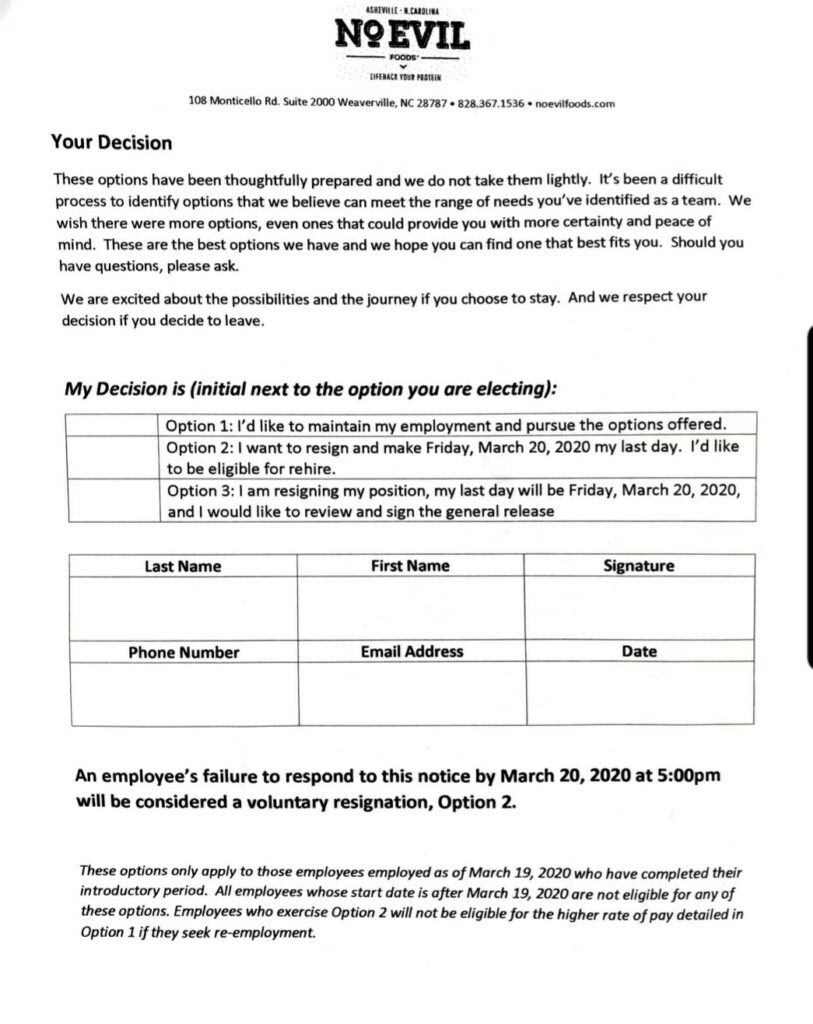

With worries growing, No Evil finally rolled out its “revolutionary” solution. Workers could choose between three options:

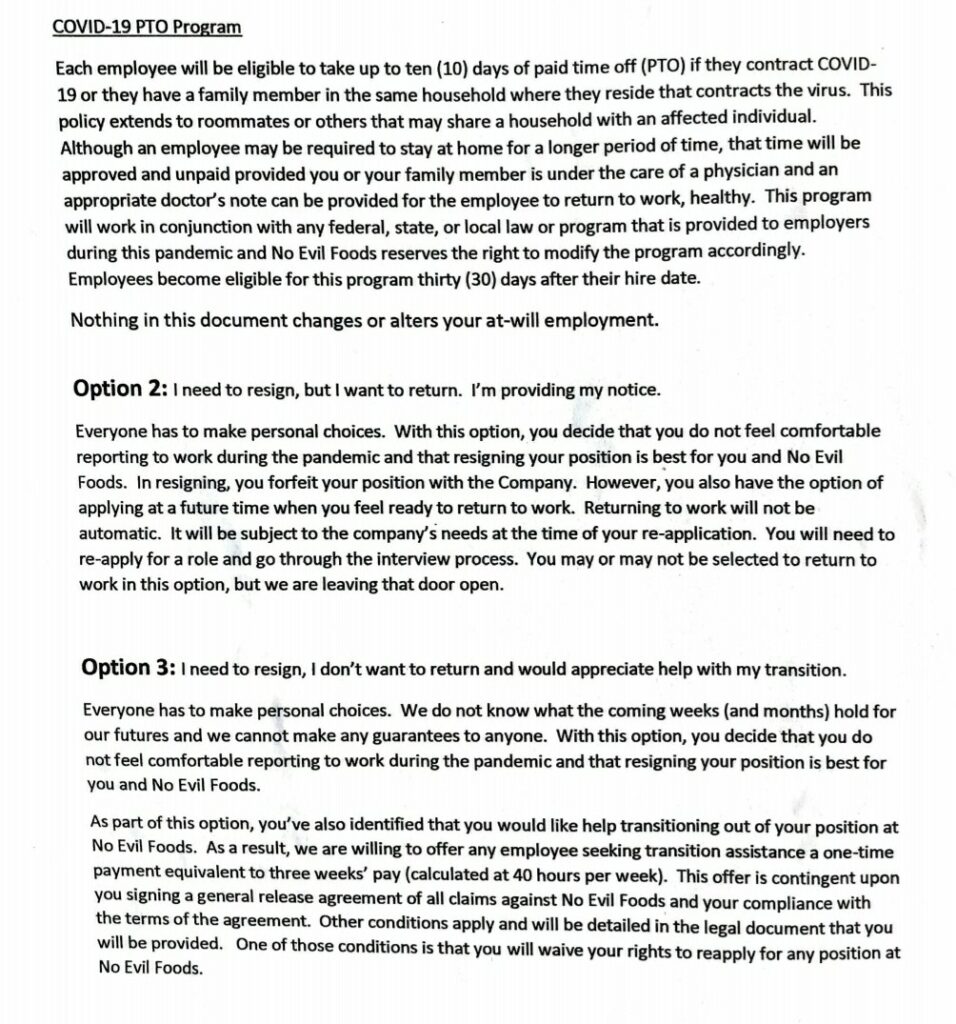

- we could take a few weeks of pay, sign away our rights to talk about our employment, sign away our rights to ever sue the company over any potential violations of the ADA, NLRA, Civil Rights Act, etc., and never have the option to get rehired

- we could quit with no payout, no gag order, and the door to reapply would be left open

- we could stay with the company and, if we each maintained 90 days of perfect attendance in the middle of a pandemic, we would be awarded temporary hazard pay

We had 24 hours to decide.

Although No Evil lost about 1/3 of its production staff following this move, I and many other union supporters ended up staying.

In the weeks that followed, many of us quickly organized a petition for immediate hazard pay which was eventually discovered by management. Before we had a chance to turn the majority-signed petition in, management jumped ahead of the idea and decided to make hazard pay immediate with no preconditions, never once crediting or mentioning the petition.

Afterward, they began firing or pushing out the remaining union organizers and petition supporters, and naturally, I was one of the casualties of this purge.

The whole experience at No Evil Foods left me with a bad taste in my mouth. I had moved to Asheville for what I expected to be a career move, and for a company selling products like “Comrade Cluck” and, until recently, “El Zapatista”, I expected their progressive marketing to align with the company’s behavior.

Not only was this wholly naive in retrospect, but more than that, my disillusionment with No Evil Foods was only a microcosm of the disillusionment that would eventually befall the greater city of Asheville as other businesses began their own nightmarish responses to the COVID-19 outbreak.

While there have been dozens of examples throughout the year, the final month of 2020 experienced perhaps two of the most offensive.

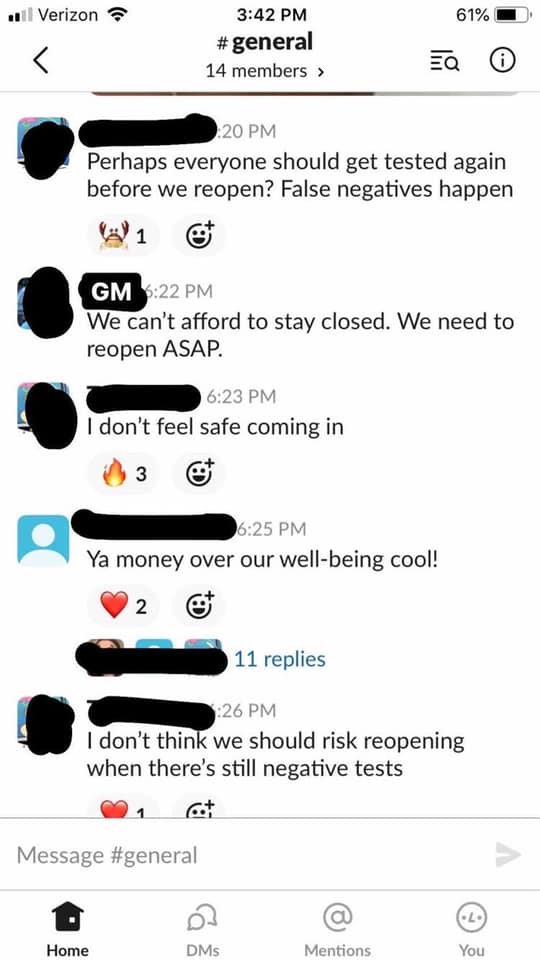

Vortex Doughnuts, described by Google as a “stylish, funky shop” offering vegan doughnut options, had one confirmed positive COVID case on December 1st, causing the business to temporarily shut its doors. On December 5th, a second worker was confirmed to have the virus. According to a Facebook post by the company, on December 6th, “all of the employees who tested negative” were “invited” back to work, but “around this time, a few employees spoke up stating they would not be returning to work without getting re-tested.”

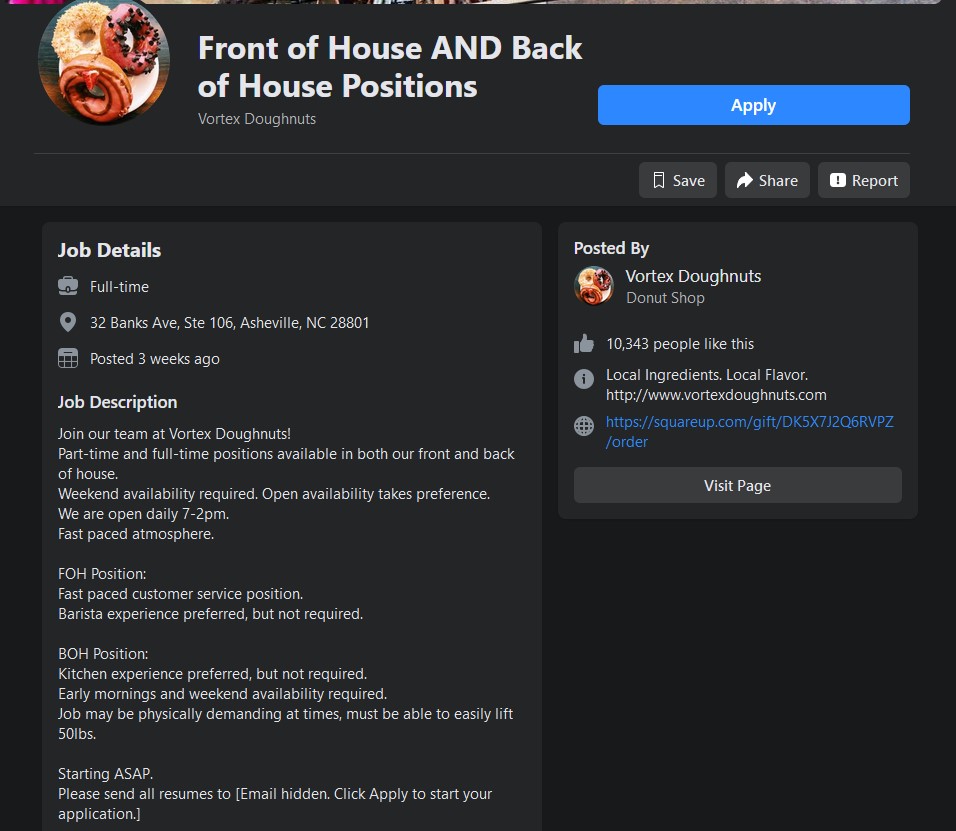

And yet, on December 7th, Vortex posted an ad for part/full-time positions for both front and back of house, starting immediately.

“We were all in the dark about the ad,” a former worker choosing to use the pseudonym “Evan” told me in a phone call. “I think it came down to the GM being upset that people had made what she considered business decisions outside of her. … I think she considered it a mutiny, people acting over her head.”

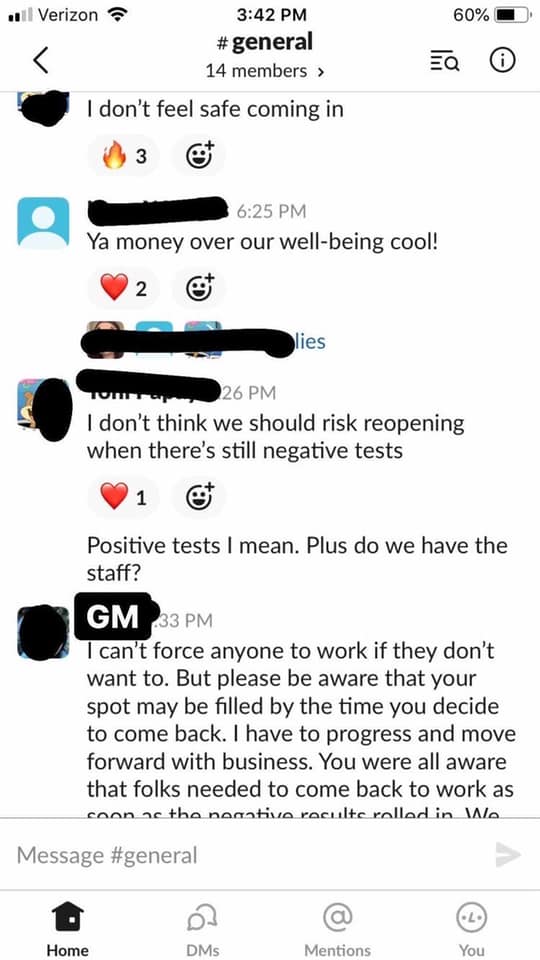

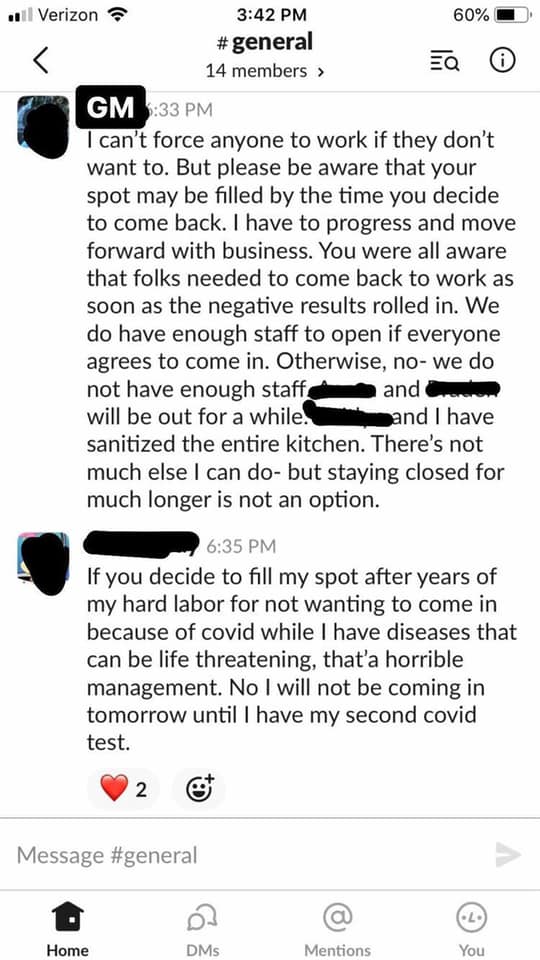

Leaked screenshots from a group chat between workers and management reveal the GM telling workers that while they can’t “force anyone to work” if they don’t “want” to, “please be aware that your spot may be filled by the time you decide to come back. I have to progress and move forward with business. You were all aware that folks needed to come back to work as soon as the negative results rolled in.”

Vortex reopened on December 10th with an entirely “covid negative staff” and wrote on social media that the employees who initially declined to return to work were “not invited back.” (Or, in less Orwellian terms, they were fired.) “We have offered references for these staff members and truly wish them the best.”

At least four workers were fired, and two have since quit.

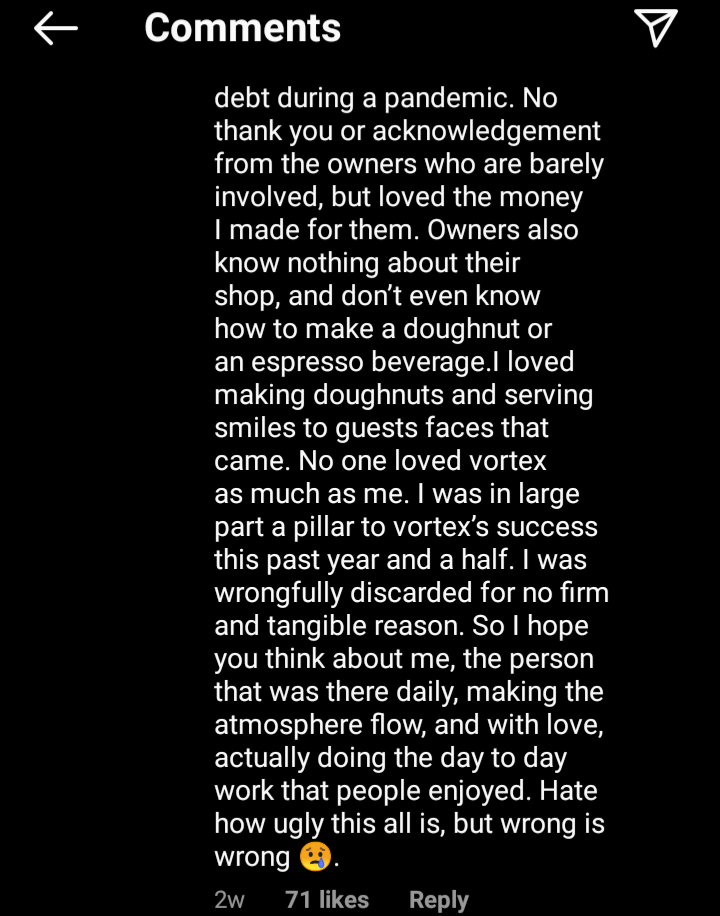

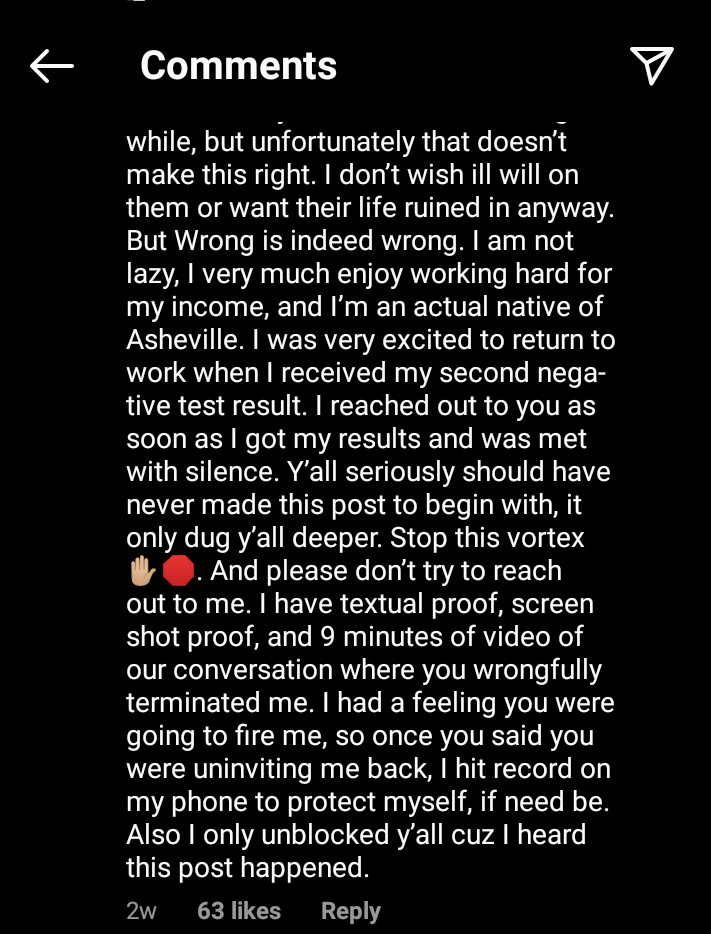

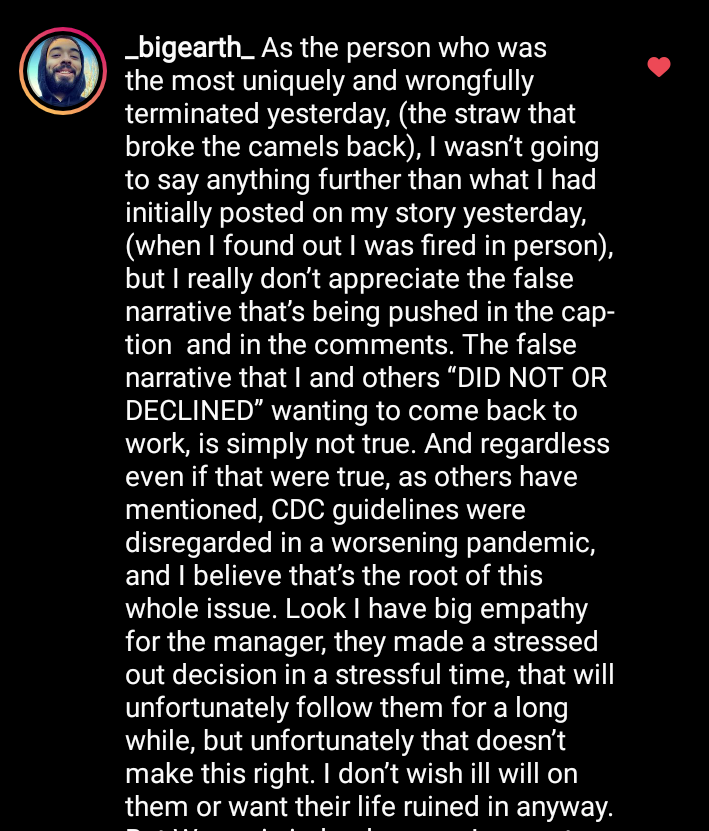

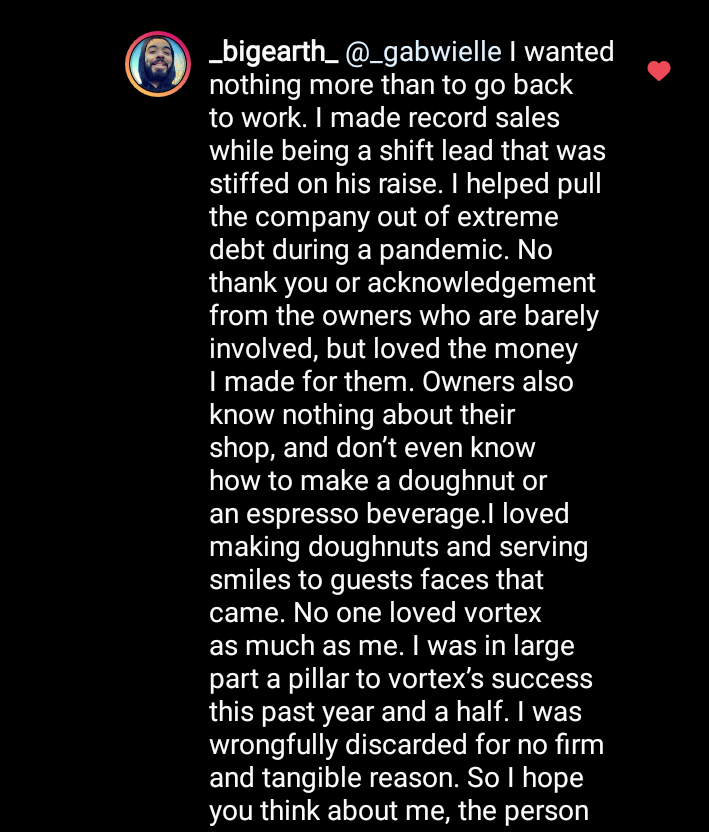

On Instagram, a former shift lead who was one of the workers fired for wanting a second COVID test wrote that “the false narrative that I and others ‘did not or declined’ wanting to come back to work is simply not true, and regardless, even if that were true, as others have mentioned, CDC guidelines were disregarded in a worsening pandemic, and I believe that’s the root of this whole issue. … I wanted nothing more than to go back to work but was wrongfully discarded for no firm and tangible reason. … I hope you think about me, the person that was there daily, making the atmosphere flow, and with love, actually doing the day-to-day work that people enjoyed.”

“I sympathize with the fact that business is very hard right now but at the same time you have to be incredibly empathetic with your staff especially when there are people in your staff who are immunocompromised,” Evan said during our conversation. “At this point businesses should have a plan in place for what to do if they need to shut down. They’ve had plenty of time to implement a structure. This could have been avoided. They have to be empathetic and listen to what the staff needs and what the community is saying.”

Several sources have confirmed that National Labor Relations Board cases have since been filed.

An email was sent to both Vortex management and its parent company for comment on this story but a reply was never received.

In one of the dozens of angry comments under the Instagram post from Vortex management trying to explain away their abysmal response to the outbreak, Cortne Roche, a former No Evil Foods worker and organizer, aptly summed up the shop’s core problem:

“This pandemic is killing hundreds of thousands and the workers you fired took that fact seriously. But the capitalist drive for dough is nuts and you’ll say anything to justify it when there is absolutely no justification.”

Elsewhere in Asheville, another example of management putting profit before workers emerged at Early Girl Eatery, a small restaurant chain describing itself as a “farm to table southern comfort food experience” with three locations scattered around the city.

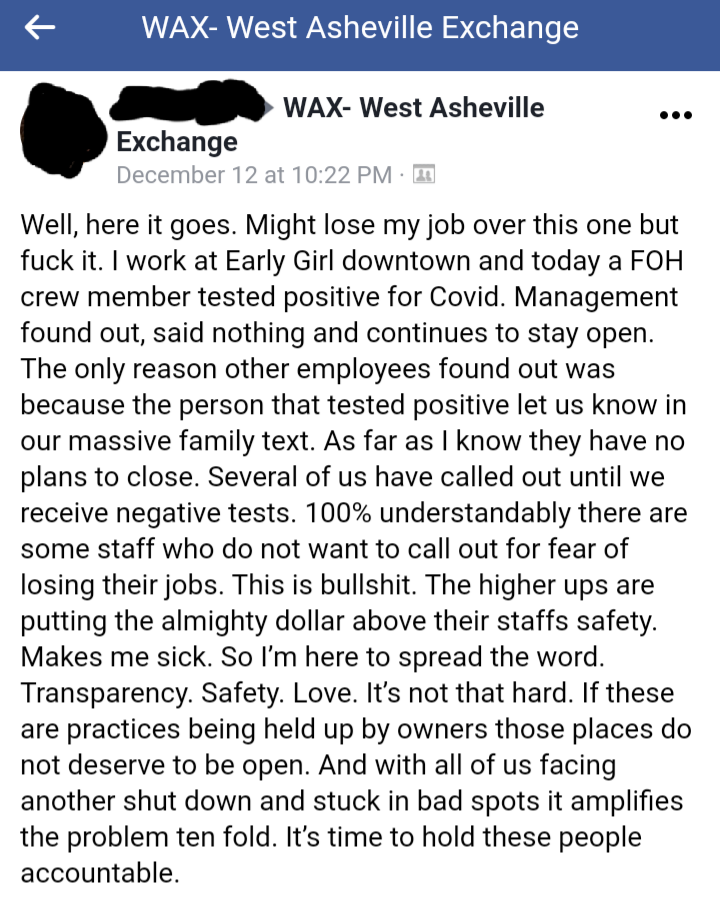

On Saturday, December 12th, a worker from Early Girl blew the whistle in the private Facebook group “WAX – West Asheville Exchange” about a positive COVID case at the downtown location:

“Management found out, said nothing, and continues to stay open. The only reason other employees found out was because the person that tested positive let us know in our massive family text. … Several of us have called out until we receive negative tests. … The higher-ups are putting the almighty dollar above their staff’s safety and it makes me sick.”

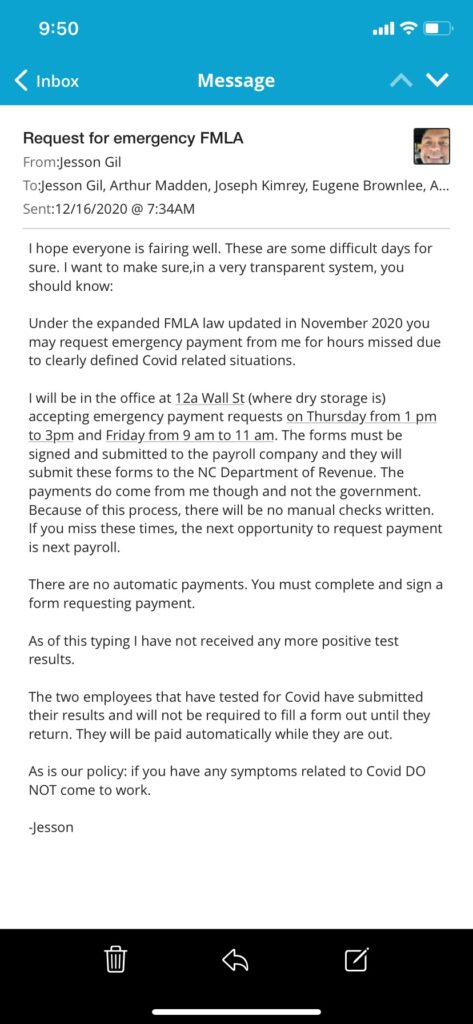

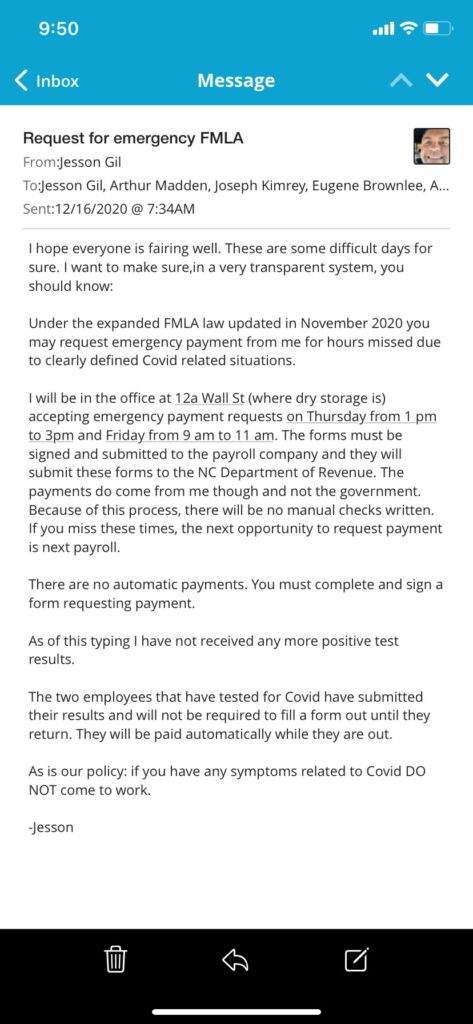

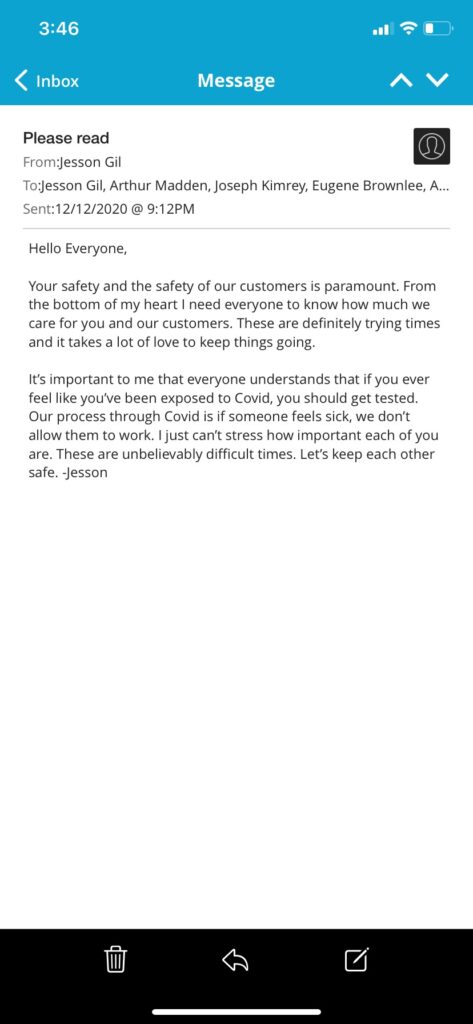

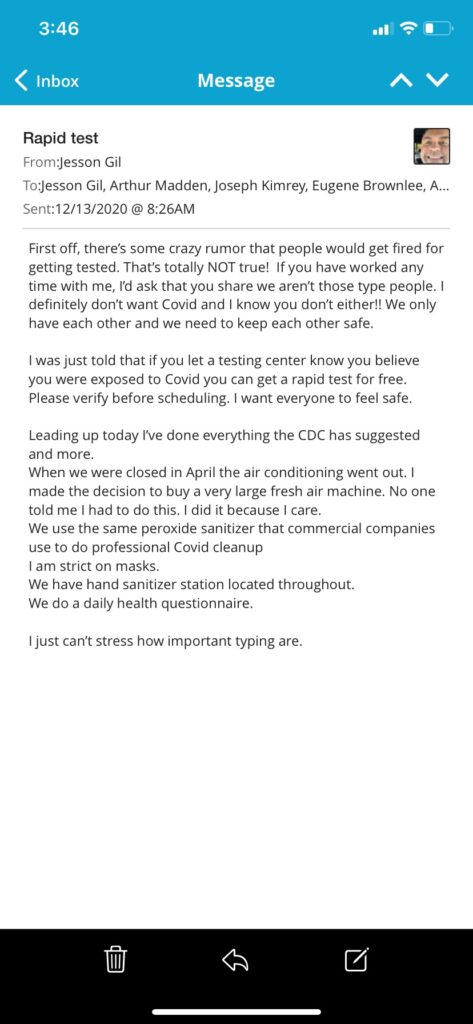

Emails sent to workers by management reveal that later in the evening, the owners told employees that if they feel sick they shouldn’t come to work, but the positive COVID case that management was made aware of earlier — and that workers knew about through their group chat — was never disclosed in the message.

The next day, Early Girl began pulling workers from their other two locations to fill the spots of those calling out at the downtown restaurant. Speaking with me over the phone, one worker from the downtown location, choosing to use the name “Kelly”, referred to this move as “insane” and went on to express understandable concerns that this decision expanded the risk from one Early Girl location to three. “They found out, they continued to stay open and didn’t say anything to any of the employees. Zero transparency.”

“Servers had been told not to tell customers to put their masks on because management feared getting negative reviews,” Kelly told me. “That was really where it started, but the positive case was the last straw.”

At around 2:30 pm, management finally sent out a third email mentioning a positive COVID case.

Ten workers from the downtown location were subsequently tested, and on Monday December 14th, another worker was confirmed to have the virus.

Early Girl shut down on the 15th for deep cleaning, on the 16th for weather-related reasons, and reopened on the 17th.

Common Themes Among the Chaos

The threads that bind what happened to me at No Evil Foods, and what happened to workers at Vortex and Early Girl, essentially boil down to two common themes: greed and recklessness, and in the midst of an unprecedented global pandemic, these two things – especially in conjunction – can have extremely deadly consequences.

Vortex, for example, presents the illusion of being a locally grown company, yet in reality, the doughnut shop is actually owned by 1000 Faces Coffee based out of Athens, GA. According to the 1000 Faces blog, the co-manager, Jay Payne, “was looking for an opportunity to move his investments out of Wall Street” and into a more “local” arena.

According to ZoomInfo, 1000 Faces has a reported revenue of $21 million, a number that might go towards explaining why Vortex was so quick to replace workers – even the ones who had loyally toiled with the company for months throughout the pandemic.

Early Girl, on the other hand, may not have millions of dollars behind it, yet the behavior of the company is nonetheless indistinguishable from Vortex.

John and Julie Stehling founded and ran Early Girl for nearly two decades before selling it off to Jesson Gil, a Texas entrepreneur, in 2018.

“When we started the restaurant, downtown was a lot of other small businesses, local people trying to build a community, very invested in what they were going to leave to their children and grandchildren,” John Stehling told Asheville’s Citizen Times in 2018. “Now a lot of the businesses that have opened up are well-funded. People are doing the right thing, but they’re not as invested in the community and where it’s going to be 100 years from now.”

I reached out to Early Girl via email for comment, and while they responded and politely declined to have a conversation, Gil’s appearance on a December 17th podcast with the business-friendly North Carolina Food and Beverage podcast offers some perspective:

“We had already had a positive COVID case, probably two months ago, and it was the first time we had anybody come back positive. There’s no handbook. This is two months ago, we get notified, and we’re like, ‘Okay, what the hell do we do?’ So we’re Googling, looking at all these things, I called the health department, I left a message. It takes them about five hours to get back to me. And the funny thing is, when I hit the five hours, I had already decided we were going to close the restaurant down.”

Gil goes on to say that when the December outbreak occurred, the “shift manager doesn’t know what to do, they’re not trained on it, never experienced it, and they’re saying, ‘Well, I don’t know what to do, let me reach out to a supervisor. They reach out to a supervisor, the supervisor sends me a message, and says, ‘Hey, give me a call.’ And this is the honest to god truth, and it’s almost embarrassing, but I was asleep. So I’m at a home, it’s the afternoon, I had a nap, and there’s a text from the supervisor.”

Kelly, the Early Girl worker I had initially interviewed for this article, offered follow-up commentary on Gil’s interview, aptly pointing out that “there should have been a plan already, especially after it happened the first time.”

Gil continues: “In that time frame, one of the people from the [worker group chat] goes on a private Facebook [thread] and posts that we’re hiding things. Nevermind that I had been asleep, and we were trying to figure something out. And so, this person posts, ‘Well, I may get fired for this, but I’m gonna go ahead and say it: They’re not doing anything.’ But we had literally just learned about it maybe two hours before.”

This narrative about Jesson only having “two hours” to figure out a response to a COVID outbreak neglects the fact that he had gone through this just a few months prior, as Kelly points out and Gil admits multiple times throughout the interview:

“And you know, we had already gone through this, two months ago. We closed, we put a statement out, and it took us four hours to do that, and we didn’t fire anybody, and I really wish that people could not have a short memory.”

Towards the end of the interview, Gil breaks down over how the December outbreak happened so close to Christmas, remarking on how his workers rely on him for a paycheck and how he’d hate for them to be sitting home without income so close to the holidays.

And yet, Gil has the audacity to close out that very same interview by casually mentioning his plans to open a fourth restaurant in Asheville at some point in 2021.

While the net revenue of Early Girl’s three locations isn’t immediately clear, Early Girl’s 2019 payroll expenses were reportedly $1.48M, which qualified the business for a Paycheck Protection Program loan from First Horizon Bank in April 2020 of a little over $300,000.

All of this taken together begs the question of why the business couldn’t afford to shut down and pay their essential workers to quarantine during an outbreak.

Gil openly admits the risk of another outbreak during the podcast, commenting that he recognizes “a lot of people” work for him, and adding that “this probably won’t be the last time.”

And it won’t be the last time.

The month of December witnessed record COVID cases in Asheville’s county of Buncombe, and it seems incredibly difficult not attributing this spike, at least in part, to the many common themes exhibited by the mostly bottom-line focused local business economy.

Such themes – encapsulated in a late-stage capitalism whirlwind of absolute recklessness and unapologetic greed – has arguably contributed to the unmasking of the city’s cool, progressive brand, especially among locals. Repairing this image can only truly begin when the many businesses that call Asheville home start focusing less on appeasing big money investors and transitory tourists and more on the essential workers who live here, work here, and continue to risk their lives for a paycheck in the middle of a pandemic.