One Wobbly’s reflections on what it took to rebuild the Richmond, Virginia branch.

The following article appears in our Summer 2019 issue. Subscribe!

I moved to Richmond, VA in the summer of 2017 with my now-wife and Fellow Worker. Once we got settled and started meeting leftists in town the general word on the street was that the Richmond branch of the IWW was defunct. I felt that this might not be correct as the social media accounts for the branch were still active, but activity was sparse. Despite persistent messaging, I was ultimately not able to get a reply from the branch media or email accounts. It wasn’t until I was wearing an IWW shirt to an event in town that someone approached me and introduced themselves as a Fellow Worker.

“Ah! I need to put you in touch with FW X!” they exclaimed.

Once I got in contact with the then-secretary I learned that, while the branch had dwindled in membership, it was indeed still active. A few weeks later we attended our first meeting and discovered the branch was about five people, well over a year behind in reports to General Headquarters, and in danger of losing its charter. I decided then it was a worthwhile task to do my part to rebuild the branch. At our next meeting I requested delegate credentials, which I was granted, which allowed me to begin recruiting and rebuilding the branch. I was later elected as branch secretary, a term that just ended for me, and am currently the communications officer of the Richmond GMB.

In what follows, I detail some of my experiences and observations from the past year and a half of rebuilding the Richmond GMB, which now sits close to sixty members, has broad appeal in the community, and contributes to local struggles. Through this mode of building the branch, we’ve hosted two fully-packed Organizer Training 101 sessions; hosted the second biennial Southern Regional Organizing Assembly; assisted a city-wide stripper strike; developed workplace campaigns in multiple industries; raised thousands of dollars in support of striking and incarcerated workers; engaged in impactful mutual aid and antiracist organizing; and — perhaps most importantly — have built a culture of care around the branch.

I’m very proud of my work with the IWW and Richmond GMB, but must make clear that it would not have been possible without my many FWs in the branch and those who mentored me as I embarked on learning how to run a branch in the first place.

Okay, enough about me. On to the good stuff:

Branch building is not the same as base building, but base building will build the branch.

The left loves to talk about the ever-elusive “base building.” Hip, older leftists will often snarl at anything they deem other-than base building — and this is often not unwarranted. The “Trump bump” saw a good deal of adventurism and macho personalities end up involved in the left, often motivated by the rush of engaging in mass action rather than a dedication to the long game of building worker’s power. Despite such criticisms, these same voices often fail to engage in base building themselves in favor of branch or party chapter building.

While branch building is certainly a noble pursuit, it is not the same as base building. First, branch building often starts by speaking to other leftists in one’s area. This is a safe and totally reasonable tactic — if you’re ever going to truly base-build, it might be easier if your organization’s local branch isn’t five people in a public library (not to disparage any branches that look like this obviously; this is where we’re coming from). But too much of simple branch building also comes with a major downside: it can turn the branch into an echo chamber. This echo chamber quickly becomes insular, growing so loud with meta-comments, inside jokes, and ironic memes (that newbies won’t understand are ironic) that it turns prospective new members off from joining the branch.

Base building, however, is an entirely different animal. In this context, base building generally refers to building a base of support, within your city or region, of working-class people not currently involved in the political or activist scene. When thinking of base building, imagine a moment in the future where your branch is well established. When you find yourselves engaged in a seriously tense public struggle against a boss, who outside of the local leftist circles will readily support you, even if just on social media? That is your base.

Proper base building takes much more time and effort than branch building and can at times seem antithetical to branch building, but it isn’t! Base building involves putting in real work and building genuine connections to people and their communities with no strings attached. In other words, if you’re really interested in the task of base building, then any material or other assistance you offer must be totally unconditional. If the person who has reached out to you for help doesn’t want to give you their email address, phone number, or even hear about your amazing 20,000 word polemic on the modern Marxist whateverthehell, help them anyway.

“We hurt because you hurt and we’re mad because you’re mad.”

In fact, it is best practice to not mention any of the above the first time you’re interacting with a person unless they openly state their interest. Just relate to them on the basic, most human levels; start with the weather or local sports if you are struggling to find a topic. I know it seems cheesy, but it works. It is absolutely crucial that your potential base sees you for who you are — just another working-class person who wants their family and everyone else to be taken care of — before they see who you as an angry radical.

I detail three specific strategies here that have been the most impactful in rebuilding the Richmond branch.

Strategy no. 1: Provide a Service

One potential way to engage in base building is to provide a service to your community that meets the above-mentioned criteria (e.g., is unconditional). I caution that it’s extremely important to do your homework before jumping into such a program. You must consult with members of the community you seek to provide said service to. In other words, find out what people need first.

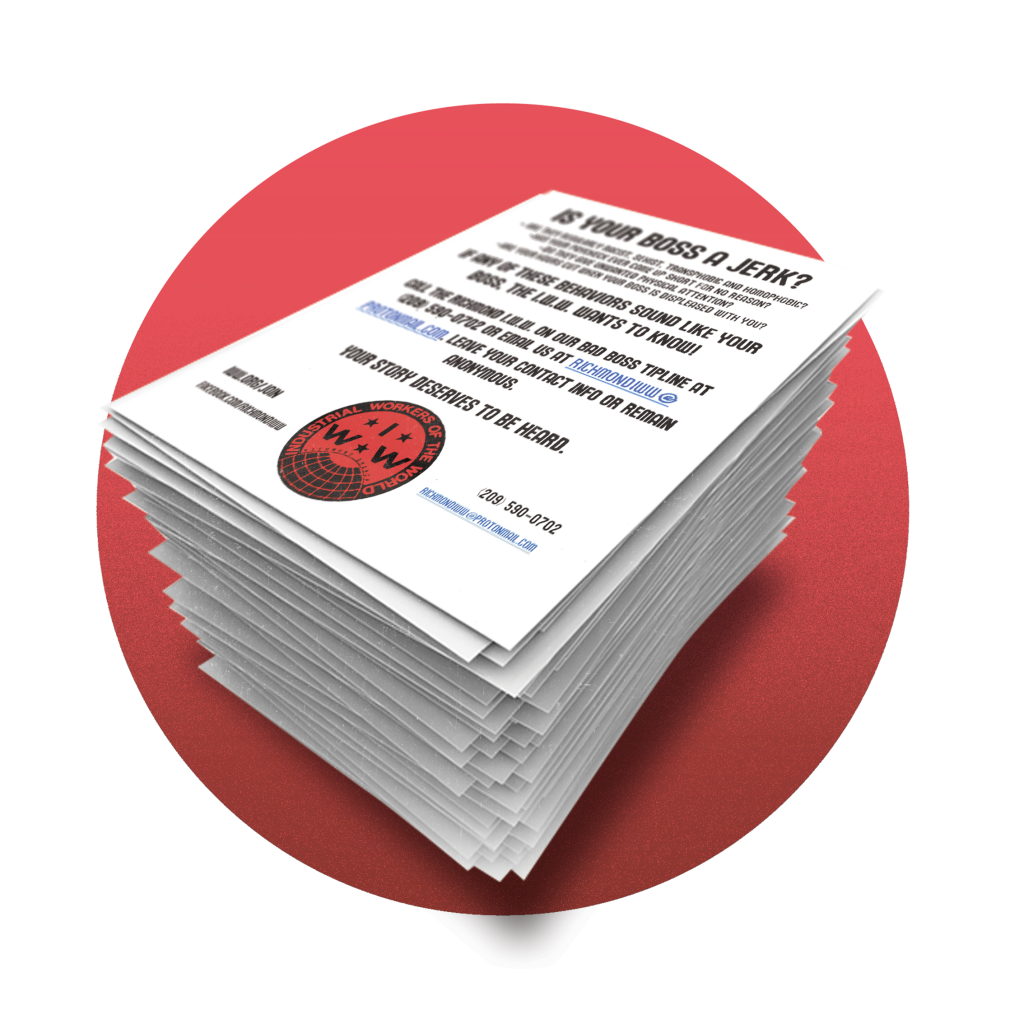

One of the first initiatives the Richmond branch recently instituted was the “Bad Boss Tipline,” a voicemail box and accompanying web form that anyone could call to report their boss to the IWW. While we were still quite a small branch at this time, we reasoned that this would at the very least give folks a listening ear – a place to call when no one else gave a damn about how their boss was treating them. It seemed like a no-nonsense thing to me at the time — let’s just put this out there and see if people call us! The tipline was initially received with mixed enthusiasm by Wobblies outside of the branch (and a few within it). Indeed, I was told by more than one FW on social media that they had tried something similar and it was a waste of time. While this sucked to hear, we pressed on and kept hanging up flyers sharing content about it on social media – and then the calls started.

I was (and still am) the primary curator of calls to the tipline. Every single person that called us and left valid contact information was then contacted by me personally. There were many cases where these folks had already left their jobs and were seeking recourse for wrongful termination or something else that had happened at work. While we didn’t have much to offer outside of advice in either case, people still seemed to be helped by having a caring ear to tell their troubles to, someone to reaffirm that yes, your boss is an asshole and your worth as a person isn’t tied to your productivity.

In other cases, folks were still employed and there were directly actionable things we could do or teach them to get the ball rolling on organizing efforts. Some of these developed into (still private) campaigns and ultimately did build the branch. By my count, the tipline has brought no less than eight members into the branch and was the source of our biggest current campaign.

Strategy no. 2: Get Involved With Local Struggles

In the summer of 2018, a black middle school teacher named Marcus-David Peters was in the midst of a mental health crisis. The police were called when he was seen running along the side of the interstate completely nude. The responding officer fatally shot Marcus despite openly acknowledging his mental state, as heard on the bodycam footage. Members of the community and Marcus’s family came together to build a strong and lasting movement called “Justice and Reformation” calling for community oversight (among many other badly needed reforms) to the Richmond police. This first community meeting following Marcus’s death was somber and difficult to attend, but when his sister spoke, she spoke incredible truth. We rallied behind this movement and joined them in the streets the following week, forming a critical mass outside of the Richmond police department in the middle of a downpour and forcefully demanding what Marcus needed so badly that day — help, not death.

In December 2018 we were contacted by members of the local Virginia Education Association (a state affiliate of the National Education Association) via the bad boss tipline. They were planning a mass walk-out and march on the capitol building here in Richmond with public school teachers from all over the state, and wanted to know if we could help. I spent the next few weeks in conference calls and Skype meetings with the folks at the core of organizing this event — a caucus group of more ambitious VEA members known as Virginia Educators United. We were able to produce literature in the form of trifolds distributed during the action and were invited into one of the middle schools in Richmond to film a short documentary which was published immediately following the march. We are currently in the process of filming more to produce a longer version that will be circulated at the beginning of the fall semester. In addition to this, some members of the VEU and other education workers have since joined the branch, leading to IU 620 quickly becoming our most populated IU grouping.

While there are certainly other examples of our involvement in local struggles in the Richmond community, these two particularly powerful experiences were most relevant to the question of base building, because they sit at important intersections of the struggles against capital and white supremacy. They are also intrinsically linked to the things every working-class person cares about the most: the health and safety of their communities. The one-on-one process that we teach in OT 101 requires that we reflect genuine empathy for the pain and suffering of the workers we engage with. As such, our involvement in community struggles must, too, reflect this principle — we hurt because you hurt and we’re mad because you’re mad. Such values are also central to generating a culture of care from within the branch, such that each member of the branch has the same potential opportunities afforded to them by union membership.

Strategy no. 3: Building a Culture of Care

By “Culture of Care” I’m speaking to some mushy-feely stuff that might feel weird or uncomfortable, kind of like watching Marianne Williamson talk for any period of time. Sit with the feeling for a second and try to pretend like it isn’t aversive when I say this — during my tenure as secretary I told everyone in the branch I loved them during my good and welfare turn at the end of each GMB meeting. Now this may feel cheesy and perhaps even inconsequential; after all saying ‘I love y’all’ once a month is just three words. But what if even just one person in the room hadn’t had anyone tell them they loved them that month? And so what if that wasn’t the case anyway? This small gesture never started out of any intentional effort — I just did it once. Then I kept doing it, because it was and still is true — I love my branch. I don’t know that this one behavior of mine had any real impact on the culture of our branch, but it certainly couldn’t have hurt.

I get the general vibe from most in the branch that the feeling is mutual to some extent — we do our very best to take care of one another. We place an emphasis on supporting one another in any way that we can, which has the effect of modeling these behaviors as social norms for new members, perpetuating this culture further. Being a hardened union militant doesn’t (and shouldn’t) preclude being a lover — especially in the case of our Fellow Workers.

For all her bizarre and downright nonsensical positions, Marianne Williamson is actually kind of right about this — capitalism has bred an utter loathing of life in each of us. It is part of our struggle against the capitalist system to find that joy again — to love and be loved. If anything, it drives the wealthy nuts to know that we can be happy without their greed and money. It makes them absolutely sick; our potential for happiness in spite of the various forms of oppression we experience is an existential threat to the upper class precisely because it invalidates their entire world view.

In closing, I hope this reflection can serve as a sort of springboard for branches looking to try some new things that may aid base building efforts and, thus, branch building. I am no expert in union building and am just now rounding my third year in the IWW, but I do know that we have achieved some degree of success and that the suggestions made in this piece are accurate representations of what led us to this point. I encourage others to try versions of the ideas that worked for us, but urge a need to reflect on how to best alter these suggestions to fit the needs of you community and branch. I also must underscore how important I believe the culture of care to be at the branch and union-wide level. If we can begin to make the IWW a space of healing on the inside it will be transformed into a fierce machine on the outside, one fueled by collective dreams of the world we wish to build.

1 thought on “Build the Base, Build the Branch”

Comments are closed.