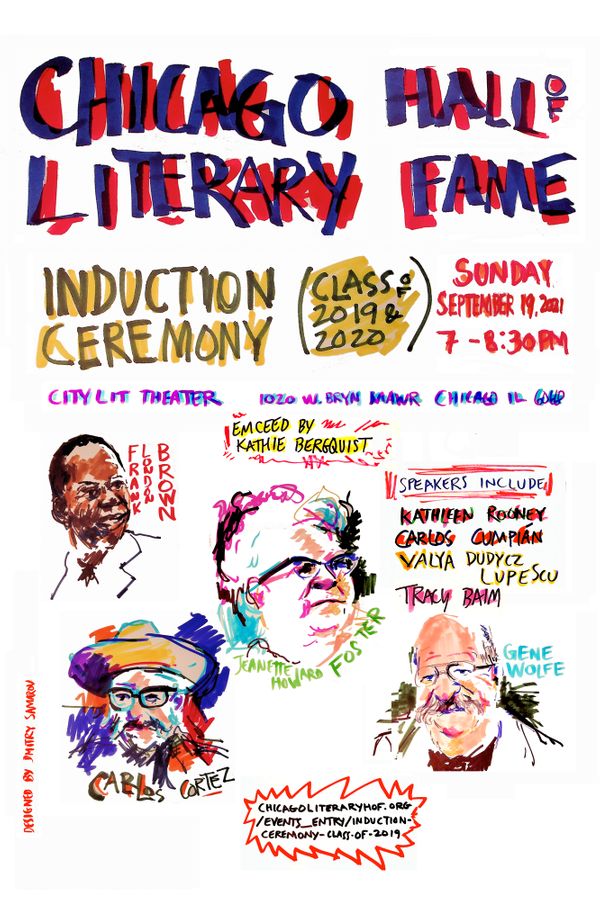

Throughout his life, Carlos Cortez memorialized many members of the Industrial Workers of the World in his iconic posters, as well as his poetry, songs, and other contributions to the IWW’s official publication, Industrial Worker. Now, Cortez himself will be memorialized by the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame, to which he will be inducted on September 19.

Born in Milwaukee in 1923, Cortez spent his childhood watching his parents organize their community with the IWW and the Socialist Party. In grade school, Cortez learned to turn his drawings into wood and linoleum cut blocks, allowing him to print as many copies as he liked. He also learned multiple languages from his neighbors, along with the struggles they faced as immigrant workers.

By World War II, Cortez had decided there was no nation worth fighting for and became a conscientious objector. The decision landed him in federal prison for two years.

“He really found his politics in prison, where he had nothing but time to read and talk about international struggles with other prisoners,” says the poet Carlos Cumpian, a close friend of Cortez.

“Cortez felt war was generally orchestrated by the rich, and he never wanted to fight other workers,” says Cumpian. “He would’ve gone to Germany to kill Hitler, but he wasn’t going to go and kill other working-class people.”

After prison, Cortez joined the IWW and found his niche through art and writing. He was drawn to accessible poetry in the same way he was drawn to easily reproducible art. Cortez focused on narrative poetry, telling the stories of the daily lives of working people. Eventually these narratives became part of a long-standing column in Industrial Worker entitled “The Left Side.” Although he wasn’t a musician himself, Cortez also has a songwriting credit in the IWW’s Little Red Songbook for “Out of Work Blues.”

Prior to leaving Milwaukee, Cortez met his wife Marianna. Together, the couple moved to Chicago, where Cortez worked various factory jobs — some with the express intent of unionizing the workplace. Cortez and Cumpian became friends around 1970, after a chance encounter.

“He invited me to go and hang out with him and his fellow workers, listening to music,” recalls Cumpian. “They let me know about a job and a bunch of us signed up. The place made lava lamps and black lights and distributed them. This ended up being my first strike.”

“[Cortez] helped lead it,” Cumpian continues. “We were able to get the truckers to respect our picket and we won. He always made sure his circle of friends were all onboard with protesting and being public about it.”

While Cortez never made a living from his writing or art, he left behind a legacy that includes both when he died in Chicago in 2005. His woodcuts and linoleum cuts were left to the National Museum of Mexican Art, with explicit instructions to reprint his work in ways that are affordable to workers.

As part of the induction into the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame, Cumpian will present a representative of the National Museum of Mexican Art with a statue of Cortez to add to the museum’s collection of his work. Don Evans, director of the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame, cites Cortez’s writing and his organizing as factors in his inclusion.

“The selection committee did consider his whole body of work,” says Evans. “Not only did he publish significant poetry, but it was connected to his lifelong mission of supporting workers, workers’ rights, artists, and the relentless pursuit of social justice.”

Find Carlos Cortez’s posters of Joe Hill, Lucy Parsons, and Ben Fletcher, as well as the Little Red Songbook, in the IWW Store!