This is Part III of a three-part series on the issue of paid staff in the union movement.

A few years ago I was solicited to apply for a staff job in the union I’m a member of and was told that if I applied I’d likely get it. On the one hand, this was a bit of an ego boost to know that I was respected enough for my organizing to get this kind of invitation. Without the job title and the status of being a “professional” organizer that comes with being paid for it, society views your efforts as less serious and merely recreational.

I also knew that if I got the organizer job that my annual income would nearly double. That certainly was appealing in some ways, but it’s not what my politics and beliefs suggested was the best way to build the union movement and create the wider social change that I sought. Being in a position where I didn’t have large financial obligations like lots of debt or needing to be a breadwinner for a family, I could turn down such a salary and stay true to my vision of change.

I don’t want to frame my decision as any kind of “self-sacrifice” on the part of the movement, and rather I feel like I’d have to make much costlier sacrifices if I took the staff job. I organize the way I do because it’s what feels natural and good, it results in material wins for myself and my coworkers, and it’s in line with my political beliefs of what it takes to build a strong and radical labor movement.

I’ve known staff with radical politics who view their organizer jobs as just jobs, who have a sober assessment of the potential and limits of what they can accomplish as staff. It’s a job to them like any other, and even though their job is to help workers improve their working conditions and maybe their political commitments enable them to bend the stick a bit more in favor of worker power than more liberal staff, they also acknowledge that they can’t overcome the constraints of capitalist unionism.

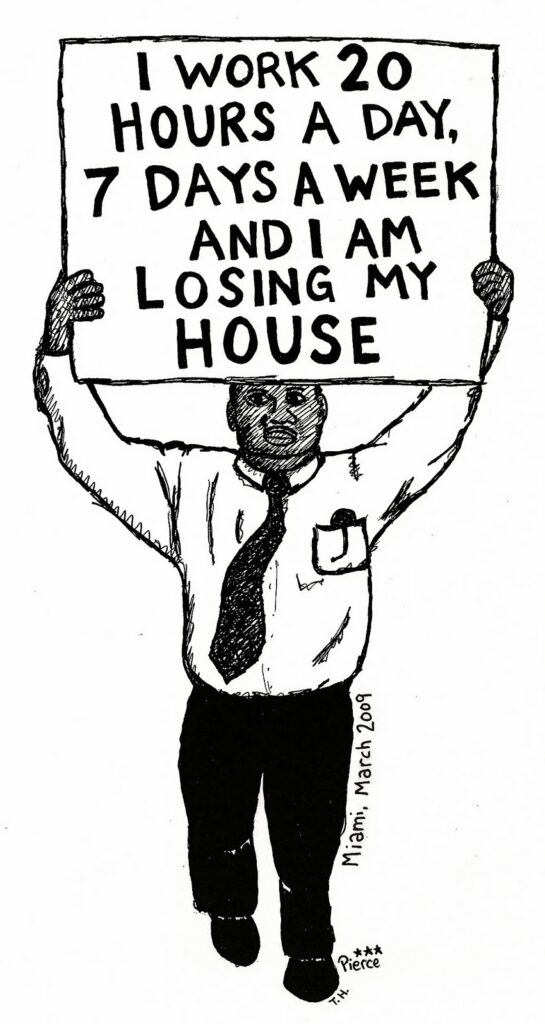

I’m definitely not against people having jobs as staff and treating those jobs as jobs, making the most of it, and getting an income to survive on and support a family with. All of my critiques against staff-based unions are not meant as any kind of moral critique of individuals merely for having staff jobs. Rather, I’m against those who implicitly see staff jobs as where the “real” and effective and radical organizing comes from and, in doing so, implicitly direct energy and legitimacy away from organizing by the rank-and-file who alone hold the power to make fundamental change by taking collective action.

As flattering as it is to be offered a labor organizing job, the qualifying skills are entirely learned. I think it’s a job anyone can get if they put the time and effort into honing their skills as an organizer. Someone who, over a couple of years, organizes with coworkers at their workplace, goes to trainings and has a community of other organizers and mentors to learn from, and reads up on some of the main ideas and history of union organizing would be qualified for such organizer jobs (many staff organizers get jobs with much less of a resume than this). Staff don’t possess unique talents or inspired wisdom that everyone else has to defer to.

As a worker organizer you sometimes don’t have as immediate access to official union resources as a staff does, such as contact lists, meeting space, training materials, and legal advice. But if your method of organizing is based more on relationships with coworkers and your collective ability to take action together, you’ll find that official union resources are not as valuable for organizing as they are often assumed to be.

Other advantages of organizing as a worker instead of as a staff include not having a boss telling you how and what to organize, as sometimes union leadership will have different priorities than you do (for example, a lot of union staff are ordered to door-knock for Democrats each election cycle); not being bound psychologically or legally to no-strike clauses in the same way that staff are; not having to self-censor your political views for fear of not representing the official union messaging; and ultimately having more freedom to organize when, how, why, and what you want to.

One of my goals in articulating these critiques is to embolden radical workers to avoid the staff route if the aim is to build the socialist movement. If you put serious energy into your organizing, at some point in your life you’ll probably be offered a staff job (or you’ll know if you apply for a staff job you have a good chance of getting one). I want people in such spots to have the confidence to say “no thanks” if they want to. I’ve known radicals who had staff jobs and left them once they came to the conclusion that they’d be more effective organizing as workers themselves. I acquired the confidence to say “no thanks” from being around a community of organizers and learning from them and constantly rubbing up against the world of paid organizers and seeing for myself the limits of such efforts in creating deeper change. I hope radical organizers can keep growing the tradition of socialist organizing that keeps its roots in the workplace, in the relationships between workers, and in the capacity of workers to take action with each other.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author. They do not purport to represent that of the IWW or Industrial Worker as a whole.

Roger Williams is an IWW member who writes about organizing at firewithfire.blog. Part III was originally published on firewithfire.blog on 11/27/2022 and has been reprinted here with permission from the author.

Contact the IWW today if you want to start organizing at your job.